Many years ago, while studying theatrical performance at Cégep de Saint-Hyacinthe, Pierre Lapointe was given a peculiar exercise by his teacher. The students were asked to walk from one end of the classroom to the other while observing their peers. Based solely on their gait, posture, and gaze, they had to assign each other certain qualities, a character, or even a profession.

Lapointe remembers being told that there was something princely about him. That was not exactly the term that this young, queer student, freshly emancipated from the Outaouais region and marked by a childhood tinged with near-chronic sadness, would have instinctively chosen for himself. Though he had been unaware of his own regal qualities, he has spent more than 20 years trying to shed this image, one he admits he may have subtly cultivated in his early days.

That, however, is proving to be a difficult task. With Dix chansons démodées pour ceux qui ont le cœur abîmé, his fifteenth full-length album, he once again asserts his boldness and classicism, solidifying his place as the Grand-duke of sensitive souls.

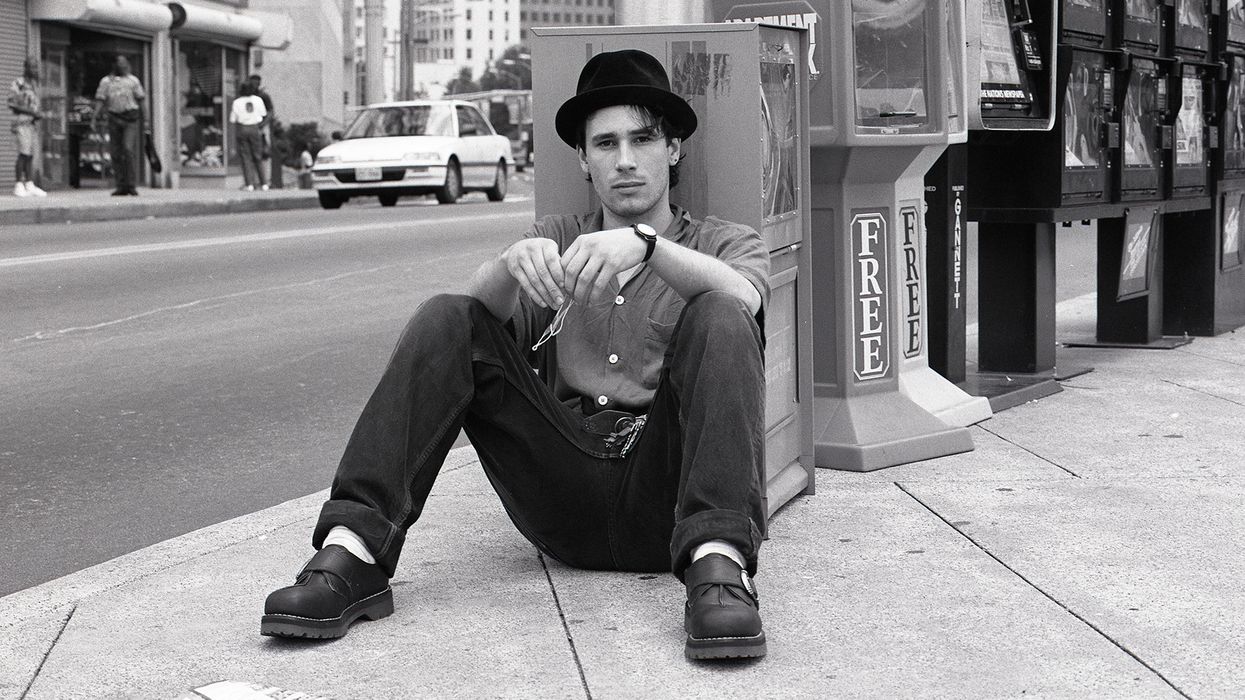

In 2004, Pierre Lapointe arrived ‘accidentally’, as he claims, onto the Quebec cultural scene with a grandiose and theatrical French Chanson, which starkly contrasted with the musical offerings of the time. Wedged between Crazy Frog, Gwen Stefani, and Simple Plan, a dandy who seemed to have been plucked from another century sang about his desire to lick every window of the columbarium, dreaming of sleeping there in peace, on a composition that sounded as if it had been borrowed from Jacques Brel himself.

Beneath Pierre Lapointe’s baroque elegance lies a mind in constant motion. From the moment his self-titled debut album found success, he never relented, continuously releasing albums, performing concerts, winning awards, and making television appearances.

But this frenzy came at a cost. Before the pandemic, the artist was pushing himself at a relentless pace.

"When everything stopped, I was heading straight into a wall. I was exhausted, I think I was on the verge of burnout. So, in a way, it was a blessing," he admits.

"My father used to ask me, whenever I talked about my schedule and how I felt, ‘But are you sleeping?’ And I’d answer, ‘Not much.’ That’s a sign that stress has taken over. He would tell me he was worried. When the pandemic hit, he was the first to say, ‘I’m glad you’re canceling everything and taking a break.’"

The timing of this break was perfect. When his longtime manager retired, Lapointe built a new team, leading to a shift in his approach, where he finally learned to do less. His new manager, Laurent Saulnier, the powerhouse behind the success of the Montreal Jazz Festival and Francofolies, gave him flak for being too prolific.

"He told me, ‘Your albums may be great, but you're saturating your own market. You release an album, and people don’t even realize it’s new. The messages are all getting mixed up.’"

For someone whose music is just one outlet for his creativity, this was a chance to return to other passions. After working on theater productions and film scores, Lapointe collaborated with Swiss visual artist Nicolas Party on L’Heure Mauve, an exhibition for which he created a soundtrack.

He also returned to drawing, having initially studied visual arts in Cégep, and designed various pieces of furniture, including a series of tables, carpets, and a Memphis-style lamp, "because the creator in me never stops." This forced break, he believes, allowed him to reconsider his approach to music and performance. He slowed down, rethought his creative process, and accepted that sometimes, less is more. Exploring other forms of art such as design, illustration, and scenography was not a diversion from music, but a complement that helps build his artistic universe. This multidisciplinary approach keeps his inspiration fresh without exhausting him. Having always envisioned his albums as total works of art, where visuals and music intertwine, Lapointe is now pushing that concept even further.

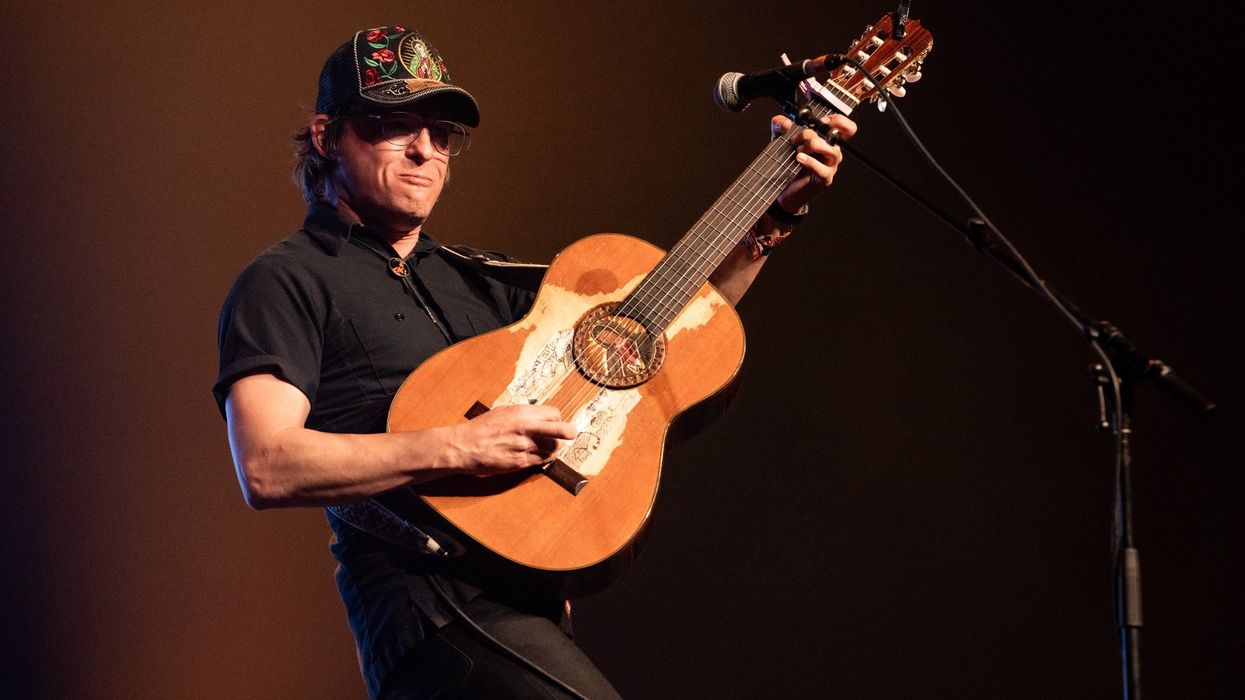

True to his love of theatricality, Lapointe has often structured his concerts as live tableaux. But the artist who once hid behind his piano now embraces a bolder, more embodied stage presence. For his upcoming show, he will stand front of stage almost the entire time, flanked by two pianists, Amélie Fortin and Marie-Christine Poirier, fully assuming his role as the central figure. This shift in stage presence stems from a broader reflection on his relationship with the audience, which has evolved over the years.

Early on, he explained that the piano acted as a shield between him and the audience, which adds another layer to ‘Toutes tes idoles’ when he sings: "You don’t like seeing people cry / It awakens the pain beneath / Of the child who grew up too fast and learned to arm himself to the teeth."

"Now, I want to be up front. I have no problem with it anymore, but back then, it was different. You have to understand that my teenage years were complicated," he confides. "I was deeply sad and depressed. I didn’t feel comfortable in my own skin, like so many teenagers. Being gay surely played a role in that. I found the world very ugly. I needed aesthetics, I needed beauty."

"Then the piano arrived. It lifted me up. It healed me. I would play notes, sometimes the same note for hours. And I would say, ‘I’m healing myself.’ The resonance calmed me. Looking back, it was a form of music therapy. I was healing through sound."

That healing process is especially evident on this album, particularly in the poignant “Comme les pigeons d’argile”, a tribute to his mother, written after her Alzheimer’s diagnosis. In “Madame Bonsoir”, he converses with the Grim Reaper, arriving, as always, at the worst possible time.

This album, however, was not originally intended for him. Lapointe explains that the songs in Dix chansons démodées pour ceux qui ont le cœur abîmé started as an exercise—an attempt to create something in the spirit of the classic French chanson he grew up with, but infused with his taste for the radical and refined. Initially, the plan was to offer these songs to other singers.

"There has never been an album where I went only halfway in a direction. When I finished writing these songs, which I had not written for myself, and then pieced them together, I realized I had to make an album out of them," he explains. "I told myself I had to go full speed ahead. The arrangements, my pronunciation—sometimes I pronounce the ‘E’ sounds like they did in the ’50s and ’60s Chanson réaliste [genre]. In the way I control my breath, in the fervor of my delivery, I went all in."

"Like Monique Leyrac, like Diane Dufresne, like Pauline Julien—artists who studied theatre, who ventured into Rive Gauche chanson [genre]. Singers who projected their voices like actresses, who could sing Kurt Weill as easily as they could sing Gilles Vigneault, but always with authority."

The Rive Gauche genre he evokes refers to the cultural movement that emerged in Paris’ left bank, in the 50s and 60s. In the heart of the Latin Quarter, intellectuals, artists and other bohemians would gather in smoky cabarets, where one could happen upon Sartre, Miles Davis, Juliette Gréco or Gainsbourg. Poetic, clamoring, theatrical; those are the songs that would come to redefine French music for the next half-century, and with which Lapointe grew up.

The result? Dix chansons démodées pour ceux qui ont le cœur abîmé has already become one of the most critically acclaimed albums of early 2025. At the time of publishing, it holds the top spot on the ADISQ sales charts.

January has been filled with constant back-and-forth travel between Québec, where Lapointe is preparing for his spring tour while also serving as the new coach on the TV series Star Académie, and France, where he has been spending several months a year.

He enjoys considerable success across the Atlantic, but more importantly, he holds the coveted status of an "Artiste"—with all the French reverence that title entails. Almost, as he jokingly puts it, as if he was more French than the French themselves.

Recently, after appearing on the hugely popular French television show Taratata, he was approached by the manager of a major French star, someone who had worked with all the greats of francophone music. "He told me that for years he had been trying to convince artists to make albums like they did in the era of Jacques Canetti, the 1960s music producer who discovered Félix Leclerc, among others. But every time, people backed out halfway, afraid to commit. He told me, ‘When I listened to your album, I felt like I was hearing a great record from that era, without compromise, yet completely contemporary.’"

Paradoxically, he also sees himself as the most Québecois of all Québec artists who have successfully exported themselves to France, when compared to figures like Garou, Isabelle Boulay, or Cœur de Pirate. "When I talk to people, they think I have a thick accent. To them, I’m unmistakably Québecois, with a very Québecois approach," says Lapointe. "(Those artists) are stars. Me, I’m a well-known singer in the Chanson world, and in a somewhat intellectual, outsider circle. The music industry, the contemporary art scene, the theatre world…"

It is true that his list of friends and collaborators is impressive. The music video for “Toutes tes idoles”, the first track on the new album, was filmed in the studio of ceramist Johan Creten. Lapointe was also invited to sing at the birthday celebration of French artist Jean-Michel Othoniel. On his Instagram feed, he is seen posing alongside the legendary Amanda Lear, Salvador Dalí’s muse.

"I have a strange status over there, one I don’t quite understand. I was named a Commander of Arts and Letters. Not a Knight—straight to Commander. I haven’t even received a medal in Québec or Canada yet!" he says, laughing. "I’m the only Canadian in history to have been immortalized by Pierre et Gilles, which is pretty funny. At the exhibition, there was Marilyn Manson and Madonna next to us. Nina Hagen was there too. And then there was Pierre Lapointe. Not Bryan Adams or Céline Dion."

There is a certain pride in his voice when he speaks about these experiences, but it is tempered by his naturally reserved nature. It is clear that Pierre Lapointe, despite his sharp pen and well-honed aesthetic sense, does not embody the role of an aloof, princely dandy. In fact, he struggles to understand how this perception took hold in the first place.

"When my success began, it completely overtook me, and my image was so strong that I could be walking down the street in sweatpants, and people would still call me ‘Sire’ and speak to me in poetic prose," he recalls. "I had only ever been to two or three poetry nights, and every time I just wanted to vomit on everyone and storm out yelling ‘You’re all so boring!’ And yet, here I was, suddenly considered a poet, with journalists asking me about Baudelaire and books I had never even read."

The dilemma in all of this is that it makes it even harder to pin down exactly who—or what—Pierre Lapointe really is. To strip him of the title of "poet" would be to overlook the raw and solemn beauty of a song like Le secret, which hides behind its bossa nova rhythms, and to forget the millions of tears shed around the world while listening to his music. And though he rejects the label of "dandy," he has nonetheless always been impeccably dressed at every one of our encounters, regardless of fatigue or illness.

The Pierre Lapointe we imagined on our television screens 20 years ago may not have been the one we thought he was. Or perhaps, he simply wasn’t that person yet.

Because despite all the sadness of his adolescence, and even though nothing was truly calculated, he feels that "there is a real symbiosis between who I knew I was and what I have done."

It was only last year, while promoting the 20th anniversary of his debut album, that he fully reconnected with the mindset he had back then. "It was as if I already knew everything that was coming," he recalls. "I knew I would work with individual artists, that I would be involved in theatre, that I would collaborate with directors, designers, architects. I knew I would travel, that I would make tons of albums, that I would go in all directions. But I hadn’t done any of it yet. When I talked to people, there was a gap between what I projected, what I said, and what I had actually done. Now, with hindsight, I understand."

In the end, perhaps Pierre Lapointe is not so much trying to escape his persona as he is trying to break free from a static image of himself—one defined by our perceptions rather than by the full scope of his talent or his desire to create something beautiful and meaningful.

By embracing, with pride, the role of the Rive Gauche crooner, he demonstrates that true audacity is not found in the medium itself, but in the sincerity of a fully and fearlessly realized artistic gesture.

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:  Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n