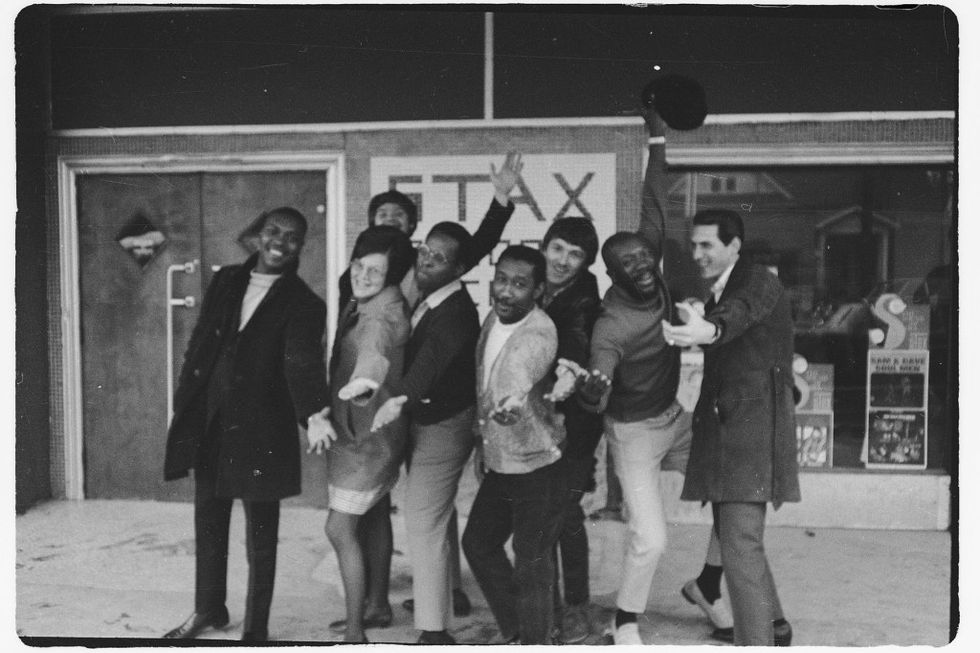

Stax: Soulsville U.S.A., Jamila Wignot’s four-part HBO documentary about the legendary Memphis record label that produced Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes, and others, offers incredible first-person stories. At one point, Booker T. Jones sits at a piano and shows exactly how he stumbled on the chords that became the 1962 chart-topper “Green Onions.”

But not long after she began working on the project, Wignot realized the story of Stax went much deeper. The label, which began (as Satellite Records) in 1957 and closed in 1975, spanned an intensely tumultuous period in American history, including the Memphis assassination Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, which prompted a profound shift in Stax’s creative direction. Ultimately, the company produced some of the most beloved soul and R&B music of all time over those 18 years, but it was not without strife.

“It’s a big American story about the destructive aspects of how business works,” she says. “The label emerged from a historical landscape that intersects with capitalism and corporate America and racism.”

Wignot previously directed Ailey, the 2021 documentary about the dance legend Alvin Ailey, and began her career working for WGBH, Boston’s PBS affiliate. She recently spoke with Rolling Stone about the nature of documentaries, deconstructing the mythology behind Stax Records, and the magic of Isaac Hayes.

There’s this mythology of Stax that it was an interracial utopia for musicians in a segregated South. How did you walk into that established narrative?

It was curious to me that this mythology had sustained itself throughout so much of the label’s history. It was also unsurprising, because, particularly in the U.S., we desperately want this mythology to be true. So when we catch glimpses of the possibility of reconciliation, it makes us feel good about ourselves. At the same time, as I spoke with many of the Stax artists, they were really wanting to reconcile their past and think deeply about what that history is for them, which was a reflection of their age and where the country is. Many of the folks we interviewed still live in Tennessee, which is a state where so much of the progress we’ve made in terms of thinking and talking about race and diversity is under siege. Also, as a person living in the 21st century, I just felt very dubious. I’m 46 years old and I haven’t ever experienced something as harmonious as what Stax said it was offering.

But the other piece of it is that that mythology is so tied to Stax’s pre-’68 era. Whereas when you look at the post-’68 period, the company is by no means less integrated. But it’s offering music that is different, distinct — people like Isaac Hayes, who are embodying a kind of Blackness that’s very proud and present and subverting tropes, like when he drapes himself in chains. So that becomes more complicated for a lot of the people who were in charge of writing the story. But if you look at Stax holistically, the complexity of the story really is there. You just have to take it in its sum and not cherry-pick the pieces that serve a very understandable desire, but one that’s not true.

At what point did you know you wanted to give equal weight to the post-’68 Stax period?

Very early on. How could you ignore Isaac Hayes, who at that time was one of the biggest and most important musicians of his era? Hot Buttered Soul is not just a fun musical work. It also blew the doors open for other musicians who up until that point hadn’t been given the expansive landscape to play in the way the album [form] lets you. There’s an argument to be made that Hot Buttered Soul is to soul music what Sgt. Pepper’s was to rock. Everything that comes after it is kind of indebted to this album that came out of this moment of crisis and experimentation, when [Stax head] Al Bell said, “Everybody must be called to contribute to this effort to rebuild our company.” He was open to letting Isaac Hayes do it his way.

And then there was Wattstax [the 1973 concert film documenting a stadium-sized performance by Stax artists commemorating the Watts riots]. It was such an incredible symbol of a company that always viewed itself as driven by more than just the bottom line. It was another way to understand how Stax was so in the vanguard even in terms of conversations about the field I’m in — moviemaking — where they’re like, “We’re not just going to be in front of the camera, we also want people to be behind the camera.” We’re very much still having those conversations today. Once I knew all of that it was like, “Oh yeah, we have to make sure to give both chapters of this story equal weight.” And that of course comes with all the heartbreaking sacrifices that come with making a music doc.

Where people say, “Where are the Staple Singers in this movie?”

Exactly, exactly.

Stax has no omniscient third-person narrator. It almost feels like an oral history with conflicting voices. How important was that approach?

That was the right tool for the job. The story is not my story to tell. It’s the story of these individuals. It’s a chorus of voices, which felt really important, because that’s what Stax was: this incredible collective endeavor, something bigger than the sum of its parts. A song like “Green Onions” comes together because of a collaborative exchange, not because somebody walked into a room and said, “OK, I wrote this, so you’re going to play this, and you’re going to play that.” I got my start working on films that ended up on the [PBS] American Experience brand, which do have that “voice of God” narrator. So, some of it was my own desire as a filmmaker to allow people to tell their stories. Documentaries reflect perspectives as much as they reflect truth. That doesn’t mean documentaries are not truthful: We fact-check our entire series, and everything is corroborated, but there is a point of view, and that’s what documentaries give.

Your Stax film feels like a movie about capitalism and industry as much as about music.

The zero-sum game of it all seems to be a part of the music industry where there’s this rapaciousness to it. That was something I felt was really important to not shy away from, because people are often not aware of what really led to the label’s demise, and it wasn’t any one thing. There was a particular kind of viciousness to the way this label went down. And Stax was a place that had given a home to somebody like Isaac Hayes but was also a place where O.B. McClinton, a Black country singer, was getting to do the music he wanted to do. The label was so open-minded and broad in the sense of what Black artists could do. It wasn’t, “We just do one thing and Black music is a monolith.” It was opening the doors to everybody. There’s a real narrowing of possibility when a label like Stax goes away, so I felt like that was an important thing for the series to ask the viewer to wrestle with.

You worked on Many Rivers to Cross, which tells 500 years of African American history. Were the storytelling challenges similar?

What makes [Stax] harder is the real people. It’s not the scholar who wrote a book. And the story doesn’t have the benefit of being so distant in time that the relationship we have to the information is clear-cut: That was bad, this was good. The people I interviewed [for Stax] were still unpacking a lot of it. They were having to go back and relive moments they had set aside and felt like they had dealt with.

Did you learn anything from working on your Tea Party documentary, 2013’s Town Hall, that felt relevant for Stax?

Every film has been an opportunity to hone my ability to sit with people in their truth and their perspective, however distinct it might be from mine. I prefer to do interviews where we spend six, seven, eight hours together. It’s an opportunity for me to try to make sense of, “Who is this person? How are they telling this story? How do they want to come across? How are they not aware of the ways they’re coming across?” There’s a knee-jerk dismissal of the talking-head interview, but there are ones that are not just soundbite-driven but are truly oral-history approaches that put the story in the hands of the people who lived it. I love being able to do that.

Is there a challenge in working on a project like this in getting seduced by your sources’ narrative?

The answer is yes, yes, and yes. But Stax is such a good mirror, in a way, of my documentary practice because I’m constantly trying to break this very stupid, white-male-invention notion of the auteur that I feel like is a thing white men love: “I did this all by myself.” No, there’s legions of people who helped you. So yes, I get seduced by seeing things from sources’ points of view, but I need to fully understand what their perspective is. That’s where the editors and producer — Ezra Edelman, Caroline Waterlow, Nicholas Ferrall, and Nigel Sinclair of White Horse Pictures — these are people who value the craft and value truth, and you can say, “I don’t know, let’s talk a look at this together.” If I actually had to do the interviews, edit them myself, make all those choices, the truth would be less resonant. It’s an occupational hazard: If you’re telling a story with people who’ve done something incredibly meaningful, more often than not they’ll be charismatic people. But I can’t speak enough about the team I had on this project.

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé

Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection  Jewelry: Personal Collection

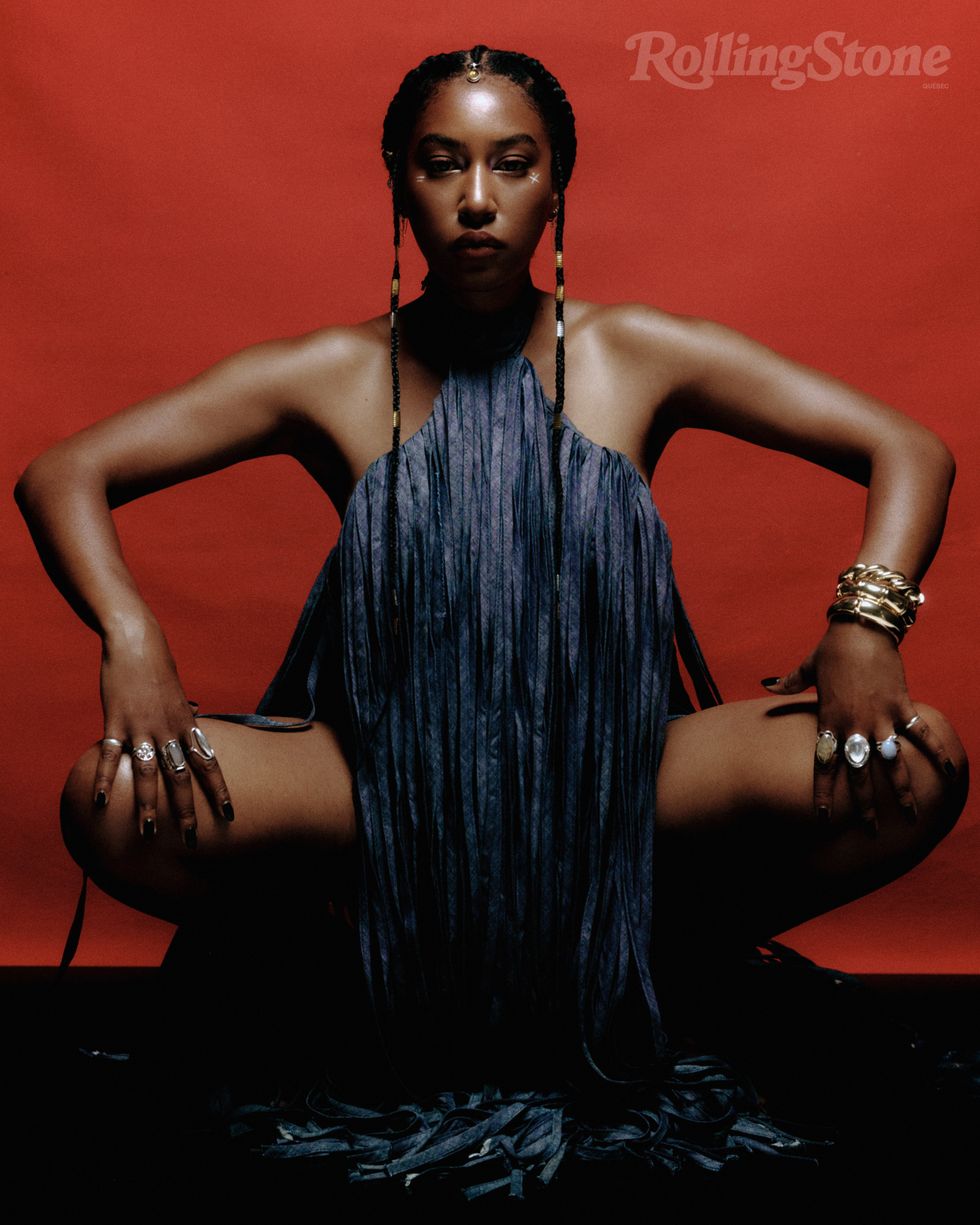

Jewelry: Personal Collection  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

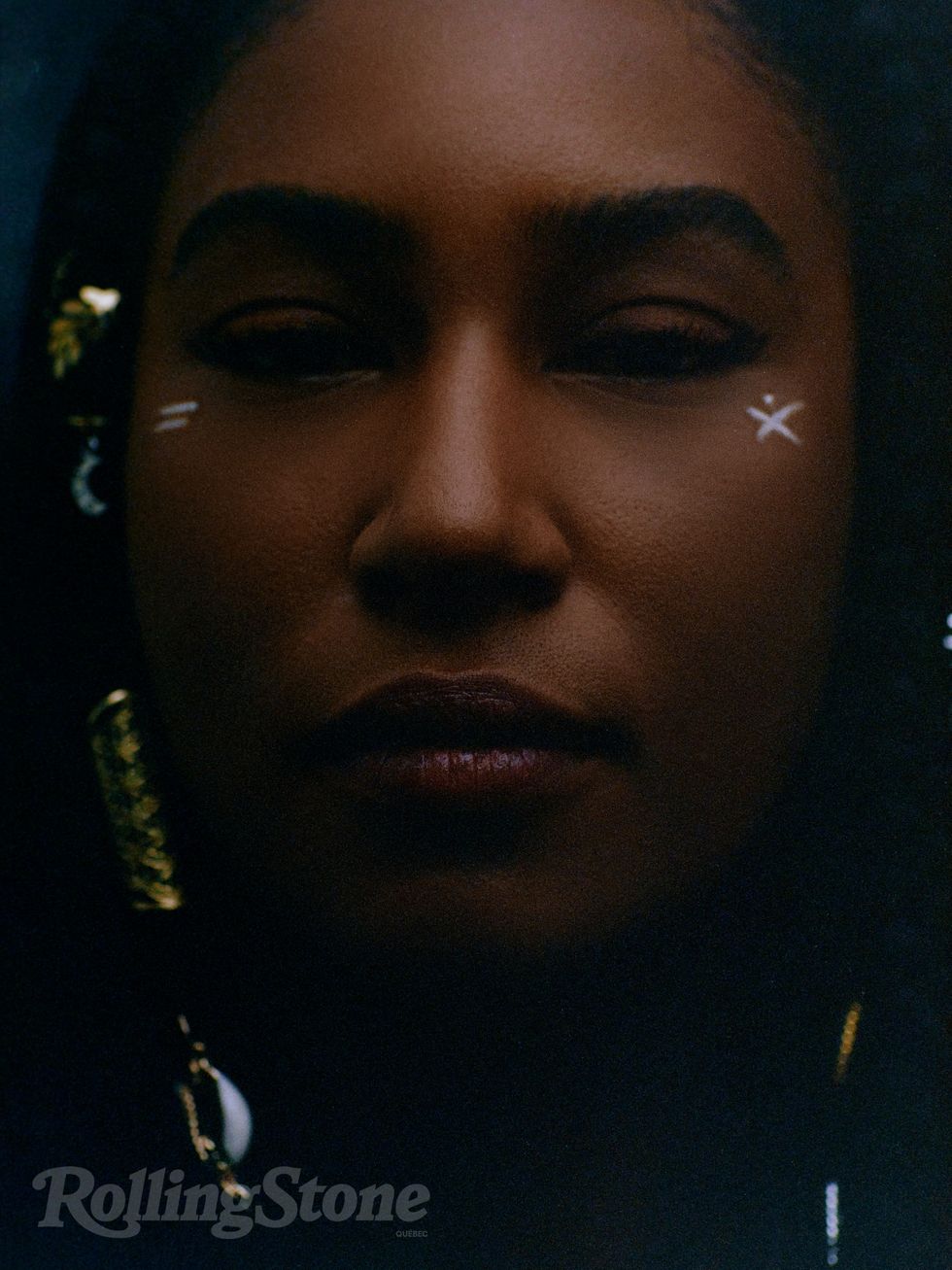

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:  Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :