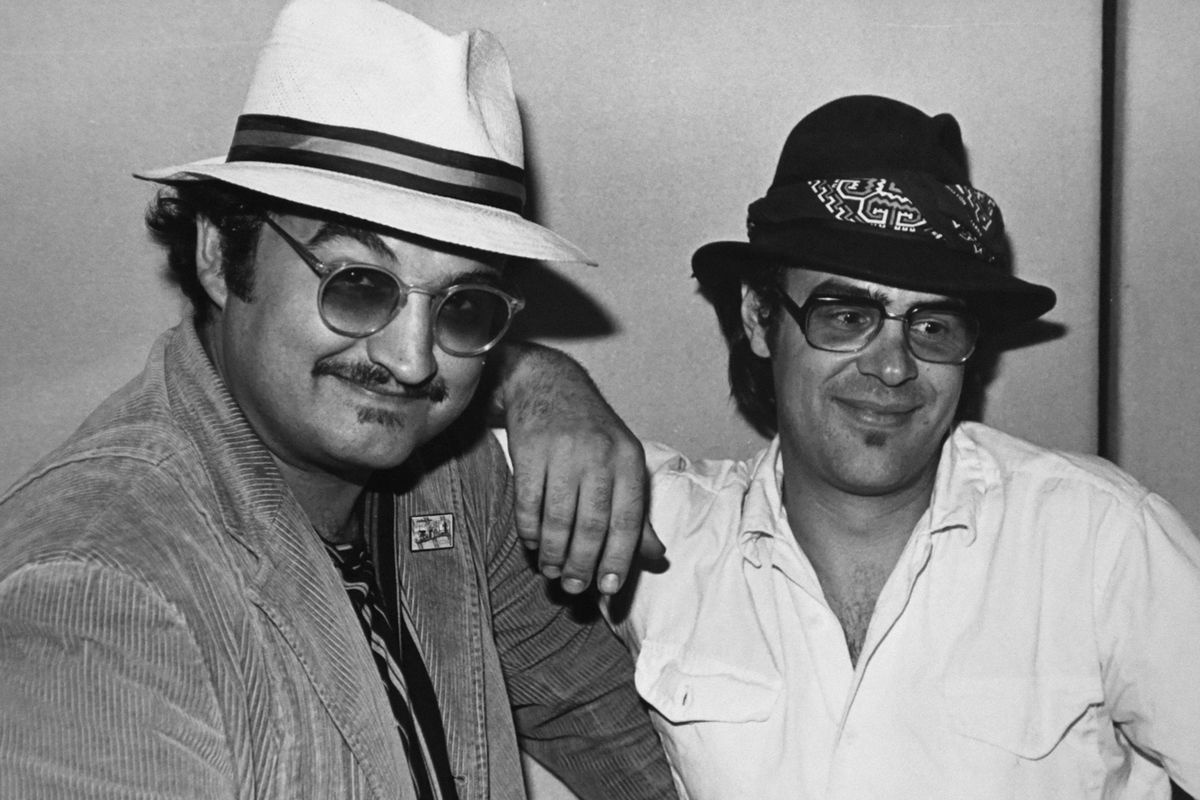

As Dan Aykroyd reminds us in his enjoyable new Audible Original, Blues Brothers: The Arc of Gratitude, there was a moment in 1978 when his friend and collaborator John Belushi was at the center of a smash-hit album, movie, and TV show, all at once. The album in question was Briefcase Full of Blues, by the Blues Brothers, Aykroyd and Belushi’s band — who went from a fun side project to a powerhouse band with their own, now-legendary movie, 1980’s The Blues Brothers. (The movie, of course, was Animal House, and the show was Saturday Night Live.) Belushi died in 1982, but Aykroyd still performs as the Blues Brothers with John’s brother, James Belushi, to this day — they have an Aug. 17 gig coming up at a Blues Brothers convention in Joliet, Ill. Aykroyd, wearing his shades and fedora, recently joined Rolling Stone on a Zoom call to look back at his time in the band and more.

How are you, man?

Hey, listen, the eyes winked open. Life is a blessing every day. I am so thankful. I am so grateful for everything good and bad that’s happened to me, and so grateful that I’m able to have the privilege of growing a little older. Many have not. Lost my brother, lost my buddy [Seattle Seahawks owner] Paul Allen, lost John [Belushi] early. We lost a lot and I’m still here, so I’m happy, fine and very grateful.

Emotionally, what was it like to throw yourself so much back into the Seventies and remember John in such detail?

Well, it was both exhilarating and I would say I had a degree of wistfulness… or there are stronger words for that. And then also to relive some of the grief, which I really had to do when I was writing the copy. It taught me that I hadn’t processed a lot of it completely.

It’s funny to remember that your original idea for the band was a little more narrow. It seems like you wanted to do straight up-blues and not so much of the soul and other stuff.

We certainly were headed that way. Although I’ve always loved jump swing — Cab Calloway, Winona Harris, Jimmie Lunceford and then Bobby Bland. So I was always thinking about that. And so when we started out, you’re absolutely right. John and I were thinking, yeah, blues, this is going to be a blues outfit with harmonica, maybe three or four players, but then you expand that with the horns and and you do songs like Johnnie Taylor’s [1968 hit] “Who’s Making Love,” and then you realize that, hey, this can be blues — but it can be a lot bigger and fatter and more fun for dancing, which was always a big part of our act. When we recruited [Steve] Cropper and [Donald “Duck] Dunn [of Booker T. and the M.G.s], who were the backbone guitar players who played behind Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, you name an artist — they were the men that dug the well. “Duck” Dunn said, “You could release a blues album, but it’s only going to sell to a certain point. You should have a soul song on there. You should have an R&B song on there. You should recut ‘Soul Man.'” So Duck Dunn broadened us.

And then once the band was together, it became, yeah, Chicago blues, great harmonica and guitar, but also hey man, this is a Memphis fusion. This was Stax/Volt and Chicago and great session players from New York venerating not only blues but Stax/Volt, R&B, and jump swing, and it became one of the great outfits of all time, with that 19-year-old-drummer, Steve Jordan, and a kind of a party atmosphere around the whole act. So that’s what really drives it — the musicianship was superb, the songs were superb, out of the African-American songbook. We presented ourselves as these ludic front men. They’re funny, they’re weird, but they’re here venerating these artists and pointing to those musicians who are the real superstars.

What do you make of the fact that Steve Jordan was the drummer in the Blues Brothers and now he’s the drummer in the Rolling Stones?

Well, aren’t they lucky to have him? Steve Jordan, he drove that record. He made that party sound for us. He was amazing. I haven’t seen the recent Stones tour, but I’ve got to get to it. I think they’re coming across Canada soon. And yeah, he’s of course one of the greatest athletic percussionists in the world and has a massive knowledge of music. And boy, we were really honored and privileged to have Steve Jordan as a Blues Brother. So the Stones are going to enjoy that. And he’s a great hang too, like one of the greatest hangs. You’ve got Keith and Ronnie, who are hang one and hang two, and Steve will be hang three for sure.

I got a sense from the audiobook that Lorne Michaels didn’t necessarily love it when the Blues Brothers performed on Saturday Night Live.

I think that it came from legitimate musicians on the show, more than Lorne. He was a big fan of “King Bee.” And that’s the first appearance of the Blues Brothers on SNL, when we did “King Bee” with the bee costumes and the hats and glasses. And we willingly did that. Although John didn’t like the Bee sketch, because he had to wear the costume.

When was the moment that you realized that when you became confident that John could front this thing, that he could be your singer?

Well, when I saw him doing Joe Cocker. And I saw the musical talent and the moves. Plus he could do anything. John at Second City was legendary. His moves were legendary there. From the first moment I met him, I had no doubts we could pull it off. We were probably the least talented vocalists or musicians in the whole outfit, but let’s rely on and point to these wonderful players behind us. And we’ll present it in a way that the audience will enjoy it with dancing and fun and humor and great songs. And we’ll front the act in tribute to stars who had really made it before and who are far more talented.

Even in the Seventies, you faced criticism for cultural appropriation. It seems like your counterargument is that the intent of your project was preservation, because the music you were trying to elevate was already falling out of fashion in the Seventies.

it was always about that — the mission from God was cultural preservation for sure. We were having fun doing it, that was definitely a strong consideration and a motivation to do it right. And we did it by elevating it up to the cinematic level. And that’s what widened and expanded the public’s perceptions of these great artists and exploded blues worldwide a little more than it already had been. We preserved James Brown and Aretha Franklin and John Lee Hooker on film, and in the second movie, Junior Wells. So, preservation for sure. The House of Blues Radio Hour has just been accepted in the Library of Congress Permanent Archives with our 2,000 interviews where we promoted blues artists and sold tickets and records for them for almost 25 years. So, yeah, for sure, preservation is where we’ve wanted to be, in terms of a prime motivation. And, well, just the fun of doing it all.

We were offered deals on the songs we sang where it was, “Hey, look, you just give them a cash payment and then you can buy all the publishing on this song. And then you can own it.” And we did not do that with any of the songs. We left the publishing where it was. We wanted to make sure that the original estates of the original artists and the original living artists got all those revenues.

It was startling to be reminded of the blatant racism that came up when it was time to distribute The Blues Brothers movie — it didn’t really get extensive distribution in places like Alabama because it featured so many Black artists. Were you surprised at the time when that came up or was it, did it match your conception of the state of things in America?

In 1980? Come on! I was surprised. We were all surprised and shocked. What? That’s the attitude in 1980? What? What?

When you wrote the first draft of the screenplay, it was a 300-plus-page document that you once said really contained at least two movies. Were you thinking that was the movie or were you just trying to get it all out on the page?

Yeah, get it all out on the page, get it all down. The Return of the Blues Brothers was the title of it. I wanted to do the first story, then the second story, and I wanted to throw in just everything that I could remember about living in Illinois and Chicago, with the urban culture of the city of Chicago as a character, and just wanted to throw that all in there. And I didn’t know how to write a screenplay. I really just did it. But I remember, even with that 350-page draft, Bob Weiss, our producer, saying he was walking through the typing pool at Universal, and there were three or four people there at electric typewriters, and they were all laughing. And Bob said, “What are you working on?” “Blues Brothers.” He came back and told me, and I said, “We’re going to be okay.” Especially with the draft that John Landis and I generated for shooting. Now, the reason it became a movie, solely I would say. is because Landis is a master director, a cinephile. He knows structure and writing and pace and is a true filmmaker. So he did a masterful job of distilling down the 350 pages. I would say of the 350 pages, we probably shot a fifth of what I had put in there.

By the time you did Ghostbusters, had that experience taught you more about how to write a screenplay?

Oh, yes, of course. Yeah. Yeah, sure. And of course, my partner was Harold Ramis.

And, obviously, on the set John probably had good days and bad days. He was in the throes of addiction. As his friend, but also a guy who was trying to get the movie made and who was so creatively invested, how did you deal with it? How hands-on did you have to be in navigating that situation?

Well, I was pretty hands on and monitoring his behavior minute to minute — and then also letting the leash out a little bit, knowing that, if I pull too hard or resisted, he would head up into the trees. He’d be gone. And so, handled him very carefully. Tried to meter the control there, which is very hard when someone likes cocaine. Meter that control, try to hide a packet now and again, and make sure there’s enough around so we get through. Or make sure there are days when it’s not done, nights when it’s not done.

I don’t remember any serious episodes where he was impaired. There was one morning I came to work and he had a fun night the night before doing whatever. That was when we were in the car on the microphone driving down with the speakers, promoting the show. “Hey you on the motorcycle” — that scene. He was a little rocked then.

But I remember we were driving by a bookstore and all of a sudden he got very animated and he said, “stop the car” in the middle of filming. So I stopped the car. He gets out of the car and he goes into a bookstore right there and runs in and comes running out after a couple of minutes. And he brings out a portrait of W. B. Yeats, the Irish poet. And in this particular portrait, it looks like me as a young man in my twenties. It’s a very similar. He said, “It’s you!” I said, “No, it’s W.B. Yeats.” So that morning I remember he was rough, but then he got animated when he saw that in the window and he thought it looked like me. [Belushi’s wife] Judy and I, we watched him very closely, but again, you couldn’t squeeze too hard or he’d pop out and run like the dough boy.

Landis says he wasn’t at a hundred percent the way he was in Animal House, but he obviously was still John and he’s obviously brilliant in the movie.

Yeah. John’s brilliant in that Blues Brothers movie. Absolutely. Some of his scenes are just great.

To what extent were there attempts at studio interference with the film itself while it was being made?

Not so much creatively, mostly on cost. Because there was really no formal budget when we went to Chicago and started work. They were very patient. In the end, the movie cost 28 million, which today is a stone bargain. And even back then, not so bad, when movie [budgets] were starting to climb through the 30s. But you got a lot of movie, and Universal owns a classic, forever. They got their money’s worth.

You had a certain amount of cultural power at that point, and you used it brilliantly. You got your sort of wildest ideas on the screen. You love blues, you love the paranormal, and you made huge movies out of those things. Did you have the sense of, “Well, I know this kind of heat doesn’t last forever. I need to grab it and do what I want to do now”?

Well, it was conscious, certainly. I was conscious of being given the opportunity and being able to come in and pitch a movie and get it made and then get it executed. Conscious of whether all this is fleeting and I better get it in fast? No, because at the time we were doing it, we were actually accomplishing these things. I never really looked at it as being a thing that would be over, because it did go on for a while in terms of my acting and writing.

Oh, for sure.

Then when it ended, it’s pretty much wound down now. Although I just was in a Ghostbusters feature film on the big screen! I’m still up there. I’m hanging around too long, I’m telling you. Now, of course, I’ve got many ideas, but I know that there’s little chance of getting them made, and I’m realistic about it. It’s the young, the younger people writing things now. The torch has been handed, but now I see how it was fleeting. I see how it went in retrospect.

Did you enjoy that time at the center of pop culture?

Quite a lot. I enjoyed these collaborations with people that I worked with. God, and I enjoyed doing films with the best in the industry. And of course, in living in Los Angeles, what a privilege to live even in the United States. It was an absolute dream to live a dream, to be — although I call myself a fortunate working actor — a movie star at the time I was. And getting my writing made and having three children with a beautiful partner and wife. And then opening House of Blues, where we got to do these spectacular concerts. I got to jam with Little Richard! I got to jam with James Brown five times. I didn’t take any of it for granted then, and don’t now.

I think you were reluctant, maybe, to make Ghostbusters 2, but I feel like you’ve always been interested in more Blues Brothers movies. It’s sad to think about, but had you imagined there were going to be more Blues Brothers movies John, even while you were making the first one?

I was writing Ghostbusters for him. I was writing a line for him when I heard that he died, so I was more expecting to move on to that. But we didn’t have a second [Blues Brothers] story in mind. No, not at the time. Now, the second movie’s a small-g good accompaniment to the first. Erykah Badu’s song was worth the price of admission. I’m glad we did that story, and I wish Jimmy [Belushi] had been in it, but everybody was good in it, and it was fun.

James Belushi says you’re always hitting him up with ideas for a new one.

Not really. Maybe in passing. But Ghostbusters 2, just since you mentioned it — no, we all wanted to make it. It was just finding the right story. And then getting [Bill] Murray to agree. Finally we were able to come up with something that all of us liked, and it just took that long to make it, but that’s a very good companion to the first one. The river of slime! No movies are perfect, and there’s a few things I would have changed in there, but it was definitely a very good companion to the first one.

The 50th anniversary of Saturday Night Live is upon us. When they do the inevitable special, is there anything in particular you’d want to do?

Well, I don’t know. I think I’d have to be invited. Can’t walk in without a pass. I’ll think about all that when and if I get an invitation, and by the way, I want to relieve Lorne formally right now of inviting me because if I go to that thing, there’s going to be 15 people that are going to want to come with me. And there’s not enough chairs, not enough tickets. I say, “Lorne, we’ll have a steak together at Wally’s instead,” and then I just spare him the angst. Because think of the hundreds of people that are going to be there. Everybody’s going to want five or 10 people to come with them. It’ll be ridiculous.

What do you hope John Belushi will be remembered for most?

Well, what he will be remembered for, we can’t change — and that’s the spectacular work that he did and the ignominious manner of his demise. So that’s all there. But I think what if you have to inform people about who he was privately: he was well read, he was warm, he was funny, he was magnetic. He was a true thousand-watt aviation lamp walking around. He had a lot of very influential friends and intelligent friends and he was one of these just magnetic individuals that you just wanted to be around, on the scale of an Elvis or a Hendrix. A super-mega-wattage personality and very funny and warm and compassionate and kind and smart in business. Just yeah, a great human being. He really was.

Speaking of people we lost, Carrie Fisher was in The Blues Brothers, and you two were involved at that point — did she have any input on that movie other than her acting?

I don’t remember anything specific, other than I was in love with her.

Who could blame you?

And just what a spirit, what a mind, what a great human being she was. She was wonderful. Just one. Her family was wonderful too. They welcomed me in L. A., her brother and Debbie at the time when we were hanging out and dating, and they just embraced me. I was, a lonely kid from Hull, Quebec, in town, and they took me in and and were very warm. Debbie Reynolds was almost my mother-in-law there.

It’s been a wild life so far, Dan.

And as I said, I’m grateful for all of it and grateful for, hopefully, tomorrow.