Obsession works like an addiction. You feed it and feed it, falling down rabbit holes, pursuing your prey with single-minded intensity. You chase the dragon, until you are indistinguishable from the beast itself and the rest of the world slowly becomes a blurry background.

The new Netflix docuseries American Conspiracy: The Octopus Murders is about a great many things: a journalist who either committed suicide or was murdered; a government surveillance software program that the Department of Justice might have stolen from its creators; a shady, scary assortment of geniuses, goons, spies, and killers with tight connections to the CIA, the NSA, and other members of the U.S. government alphabet soup. At it’s best, however, it’s about that unquenchable obsession, the kind that can lead down dark tunnels and into sprawling conspiracy webs and ultimately death. It’s a significant cut above most true crime fare, aesthetically and especially thematically.

The two seekers here run along parallel lines. There’s Danny Casolaro, a suburban dad and investigative reporter who started digging into INSLAW, an Eighties tech company that designed the surveillance software in question and ended up knee-deep in a conspiracy web that would make Oliver Stone blush. He was found dead in a Virginia hotel room, his wrists slashed open, in 1991. And there’s Christian Hansen, a photojournalist who grabs hold of the Casolaro story and simply can’t let go. He takes director Zachary Treitz along for the ride; much of the four-part series consists of the two men chasing leads, connecting dots, and getting sucked into the maelstrom.

Absolutely not to be confused with the Oscar-winning documentary My Octopus Teacher, The Octopus Murders casts a shadow of plausibility, much of it concerning what the U.S. government is capable of, that should give viewers pause. Maybe you won’t be convinced that Casolaro’s trail leads to the October Surprise — the theory that argues Ronald Reagan cut a deal with Iran to keep U.S. hostages captive until after the 1980 presidential election, thereby making incumbent Jimmy Carter look weak and ineffectual. Perhaps it’s a bridge too far to suggest that former president (and former CIA director George H.W. Bush) was a tentacle of the figurative octopus.

But there are still assassins, henchmen, and dirty trickers galore here, all doing their secretive part for the red, white, and blue. Was Casolaro murdered because he got too close to the truth, or did the Sisyphean story (and a pile of debt) drive him over the edge? The Octopus Murders lets the question hover in uncertainty and ambiguity. It doesn’t force the issue, an approach that earns the filmmakers a level of trust and respect. Casolaro’s death is a big part of the story and certainly the catalyst for Hansen’s journey. But this is not a whodunnit. It’s a trek into a many-valved heart of darkness.

The filmmakers conjure the uneasiness of long drives down foggy roads to meet sketchy sources who might provide more questions than answers. They use editing to blur the lines between Casolaro and Hansen, two men consumed by work that often merely leads to more work; Hansen even plays Casolaro in reenactments. The score, composed by Jose A. Parody, accentuates all moods, from gloom and terror to determination and exasperation. This never feels like a Netflix quickie. You get the sense that the Octopus team, including executive producers Jay and Mark Duplass, was given the time and support to create what they wanted.

The most colorful and problematic source, for both Casolaro and Hansen, is one Michael Riconosciuto, a heavy-set former tech prodigy-turned-drug manufacturer and government operative who drops kernels of truth between what sound like madman ravings. To use a JFK analogy, he’s the series’ David Ferrie, a delusional paranoiac who also happens to know a lot of valuable things. Doug Vaughan, another investigative journalist who appears in the series, explains that Riconosciuto “fits the pattern of people who spin stories that are only partially true, that confuse at best. And confusion has its purpose because it creates doubt and, ultimately, paralysis.” Scrape its surface a little and you’ll find that The Octopus Murders is largely concerned with that confusion, doubt, and paralysis — and the horrors they are designed to obscure.

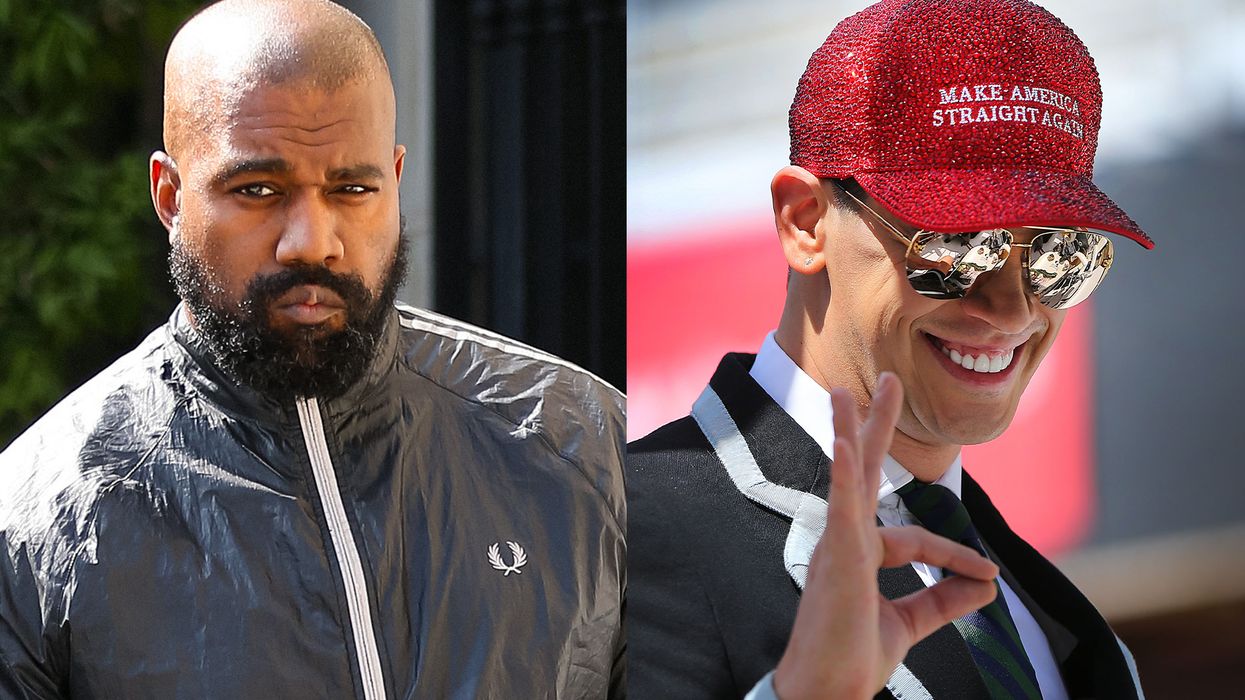

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection

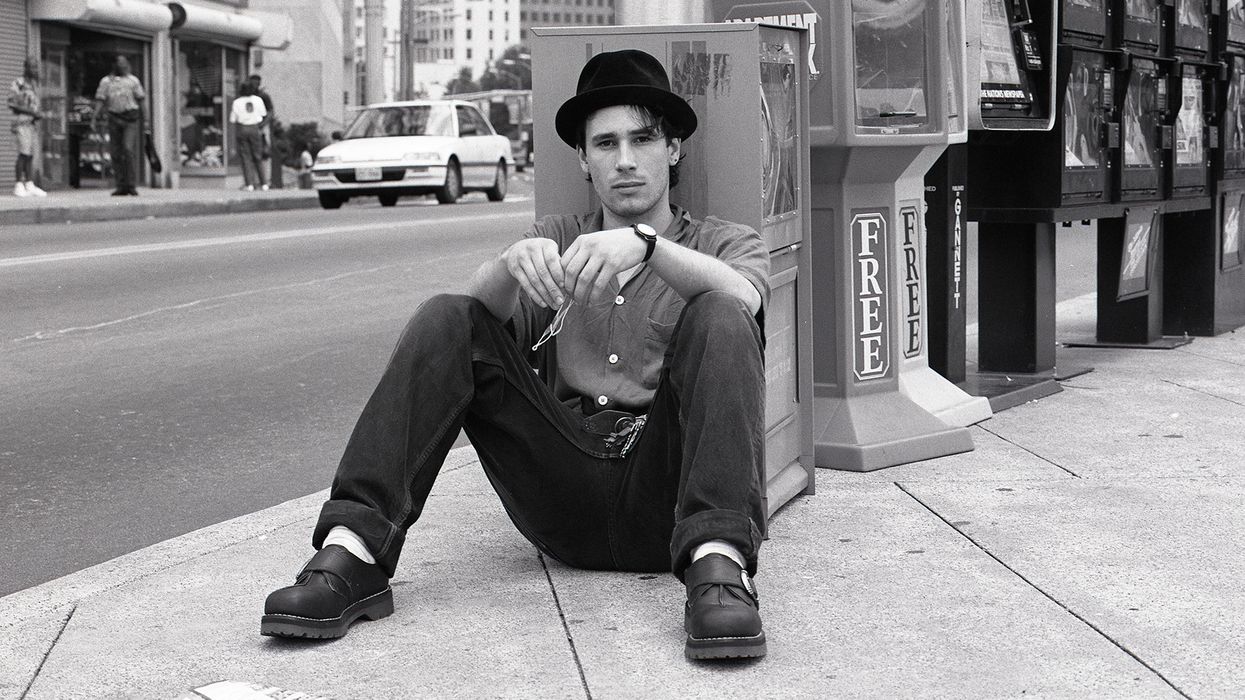

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé

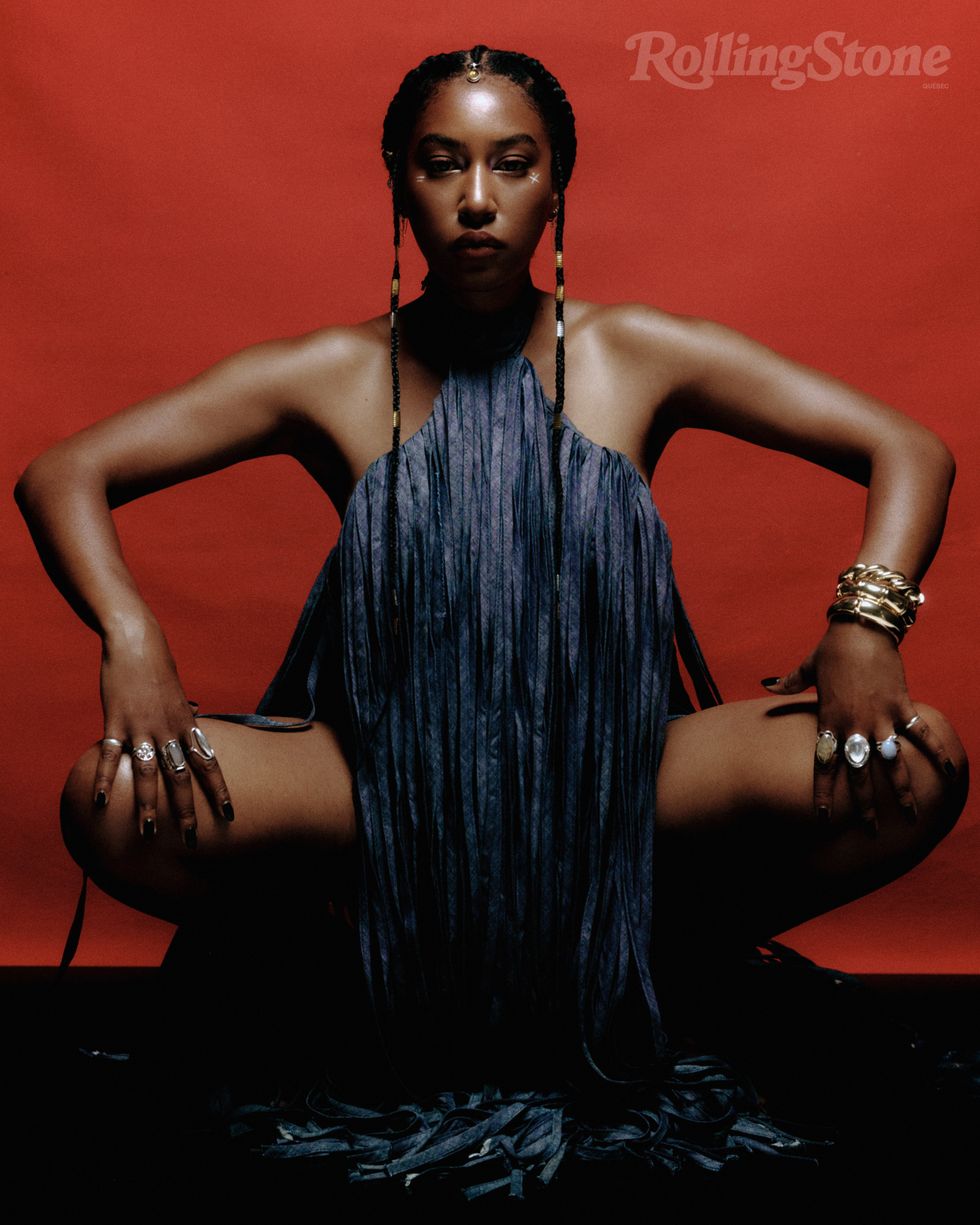

Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

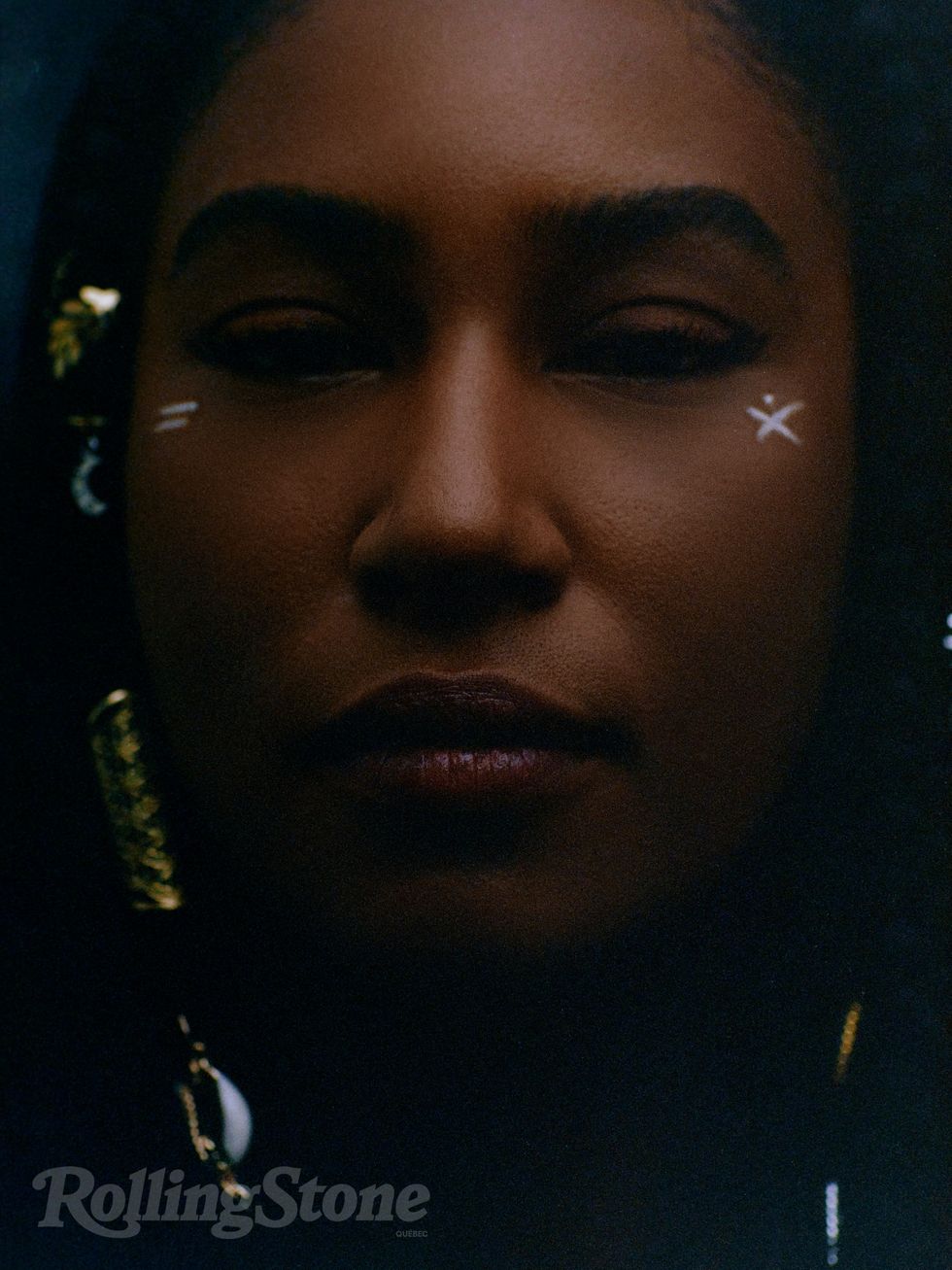

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection  Jewelry: Personal Collection

Jewelry: Personal Collection  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:  Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :