Elon Musk recently made headlines when he posted a deepfake video of Vice President Kamala Harris, with manipulated audio to make it sound like she called herself the “ultimate diversity hire” who doesn’t know the “first thing about running the country.” A month earlier, a Republican congressional candidate in Michigan posted a TikTok using the AI-generated voice of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to say he’d come back from the dead to endorse Anthony Hudson. In January, President Joe Biden’s voice was replicated using artificial intelligence to send a fake robocall to thousands of people in New Hampshire, urging them not to vote in the state’s primary the following day.

AI experts and lawmakers have been sounding the alarm, demanding more regulation as artificial intelligence is used to supercharge disinformation and misinformation. Now, it’s three months before the presidential election and the United States is ill-prepared to handle a potential onslaught of fake content heading our way.

Digitally-altered images — also known as deepfakes — have been around for decades, but, thanks to generative AI, they are now exponentially easier to make and harder to detect. As the threshold for making deepfakes has lowered, they are now being produced at scale and are increasingly more difficult to regulate. To make matters more challenging, government agencies are fighting about when and how to regulate this technology — if at all — and AI experts worry that a failure to act could have a devastating impact on our democracy. Some officials are proposing basice regulations that would disclose when AI is used in political ads, but Republican political appointees are standing in the way.

“Any time that you’re dealing with misinformation or disinformation intervening in elections, we need to imagine that it’s a kind of voter suppression,” says Dr. Alondra Nelson. Nelson was the deputy director and acting director of Joe Biden’s White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and led the creation of the AI Bill of Rights. She says that AI misinformation is “keeping people from having a reliable information environment in which they can make decisions about pretty important issues in their lives.” Rather than stopping people from getting to the polls to vote, she says, this new type of voter suppression is an “insidious, slow erosion of people’s trust in the truth” which affects their trust in the legitimacy of institutions and the government.

Nelson says that the fact that Musk’s deepfake video post is still up online proves that we cannot count on companies to abide by their own rules about misinformation. “There have to be clear guardrails, clear bright lines about what’s acceptable and not acceptable on the part of individual actors and companies, and consequences for that behavior.”

Multiple states have passed regulations on AI-generated deepfakes in elections, but federal regulations are harder to come by. This month, the Federal Communications Commission is accepting public comments on the agency’s proposed rules to require advertisers disclose when AI technology is used in political ads on radio and television. (The FCC does not have jurisdiction over online content.)

Since the 1930s, the FCC has required TV and radio stations to keep a record of information about who’s buying campaign ads and how much they paid. Now, the agency is proposing adding a question asking whether AI was used in the production of the ad. The proposal wouldn’t prohibit the use of AI in ads; it would simply ask if AI was used.

“We have this national tool that has existed for decades,” FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel tells Rolling Stone in a phone interview. “We decided that now is a good time to try to modernize it in a really simple way, when I think a lot of voters just want to know: are you using this technology? Yes or no?”

Rosenworcel says there is a lot of work to be done when it comes to AI and misinformation. She points to the fake Biden robocall, which the FCC responded to by invoking the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991, which restricts the use of artificial voices in telephone calls. The FCC then worked with the New Hampshire attorney general, who brought criminal charges against the man who created the robocall.

“You’ve got to start somewhere and I don’t think we should let the perfect be the enemy of the good,” says Rosenworcel. “I think building on a foundation that’s been around for decades is a good place to start.”

The Federal Election Commission’s Republican chairman Sean Cooksey opposes the FCC’s latest proposal, claiming it would “sow chaos” since it is so close to an election.

“Every American should be disturbed that the Democrat-controlled FCC is pushing ahead with its radical plan to change the rules on political ads mere weeks before the general election,” Cooksey said in a written statement to Rolling Stone. “Not only would these vague rules intrude on the Federal Election Commission’s jurisdiction, but they would sow chaos among political campaigns and confuse voters before they head to the polls. The FCC should abandon this misguided proposal.”

The FEC has for years routinely deadlocked on matters as Republicans on the commission have worked to prevent new regulation on nearly anything for years.

The watchdog group Public Citizen petitioned the FEC to engage in a rulemaking on artificial intelligence, and in the past Cooksey said the agency would have an update in early summer.

Cooksey told Axios that the FEC won’t move to regulate AI in political advertising this year, and the commission is set to vote on closing out Public Citizen’s petition on Aug. 15. “The better approach is for the FEC to wait for direction from Congress and to study how AI is actually used on the ground before considering any new rules,” Cooksey told the outlet, adding that the agency “will continue to enforce its existing regulations against fraudulent misrepresentation of campaign authority regardless of the medium.”

AI experts believe that action needs to be taken, urgently. “We’re not going to be able to solve all of these problems,” says Nelson, adding that there’s no silver bullet answer to fix all AI-enabled deepfakes. “I think we often come to the problem space of AI with that kind of perspective as opposed to saying, unfortunately there’s always going to be crime and we can’t stop it, but what we can do is add friction. We can make sure that people have consequences on the other side of their bad behavior that we hope can be mitigating.”

Rep. Yvette Clarke (D-N.Y.) has been calling for congressional legislation on artificial intelligence for years. A bipartisan bill targeting non-consensual deepfake AI porn recently passed the Senate.

“It was inevitable that these new technologies, particularly AI, that enable you to distort imagery and voices, would be weaponized at some stage to provide confusion, misinformation, disinformation to the American people,” says Clarke.

“[There’s] no way of truly discerning a fabricated picture versus something that is factual and real, [which] puts the American people at a disadvantage, particularly in these no-holds-barred campaigning.”

Clarke introduced the REAL Political Ads Act in May 2023, to require campaign ads to disclose and digitally watermark videos or images in ads created by generative AI. “We’ve gotten quite a few co-sponsors of the legislation, but it hasn’t been moved by the [Republican] majority on the Energy and Commerce Committee,” says Clarke.

“It’s an open field for those who want to create misinformation and disinformation right now, because there’s nothing that regulates it,” says Clarke. She points out that she’s also working on this with the Congressional Black Caucus, given the fact marginalized communities and minorities are often disproportionately the targets of misinformation. “We’re behind the curve here in the United States, and I’m doing everything I can to push us into the future as rapidly as possible.”

Dr. Rumman Chowdhury used to run ethical AI for X (formerly Twitter) before Musk took over and is now the U.S. Science Envoy of Artificial Intelligence. She says the broader issue at hand is that America is at a dangerous, all-time low of trust in the government, elections, and communication institutions. She says the FEC could be further eroding its own credibility by not taking action.

“Here we are in a state of crisis about the institutions and government which we should trust, and they’re going to sit on their hands and be like, ‘We don’t know if we should do something?’” says Chowdhury. “If they are not seen as doing something about deepfakes, this may actually further tarnish the image they have from the American people.”

As for Musk’s specific sharing of the Harris deepfake, Chowdhury says she doesn’t know why people are so surprised that he’s doing it. Musk has turned X (formerly Twitter) into a misinformation machine since he took over the platform.

“Is it terrible? Absolutely,” says Chowdhury. “But it’s kind of like we’re the people at the face-eating leopards party. You’re going to be mad because this man is doing exactly what he said he was going to do? If you’re upset, then literally, don’t be on Twitter. Or know that if you are on the platform, you are complicit in allowing this man to manipulate the course of democracy.”

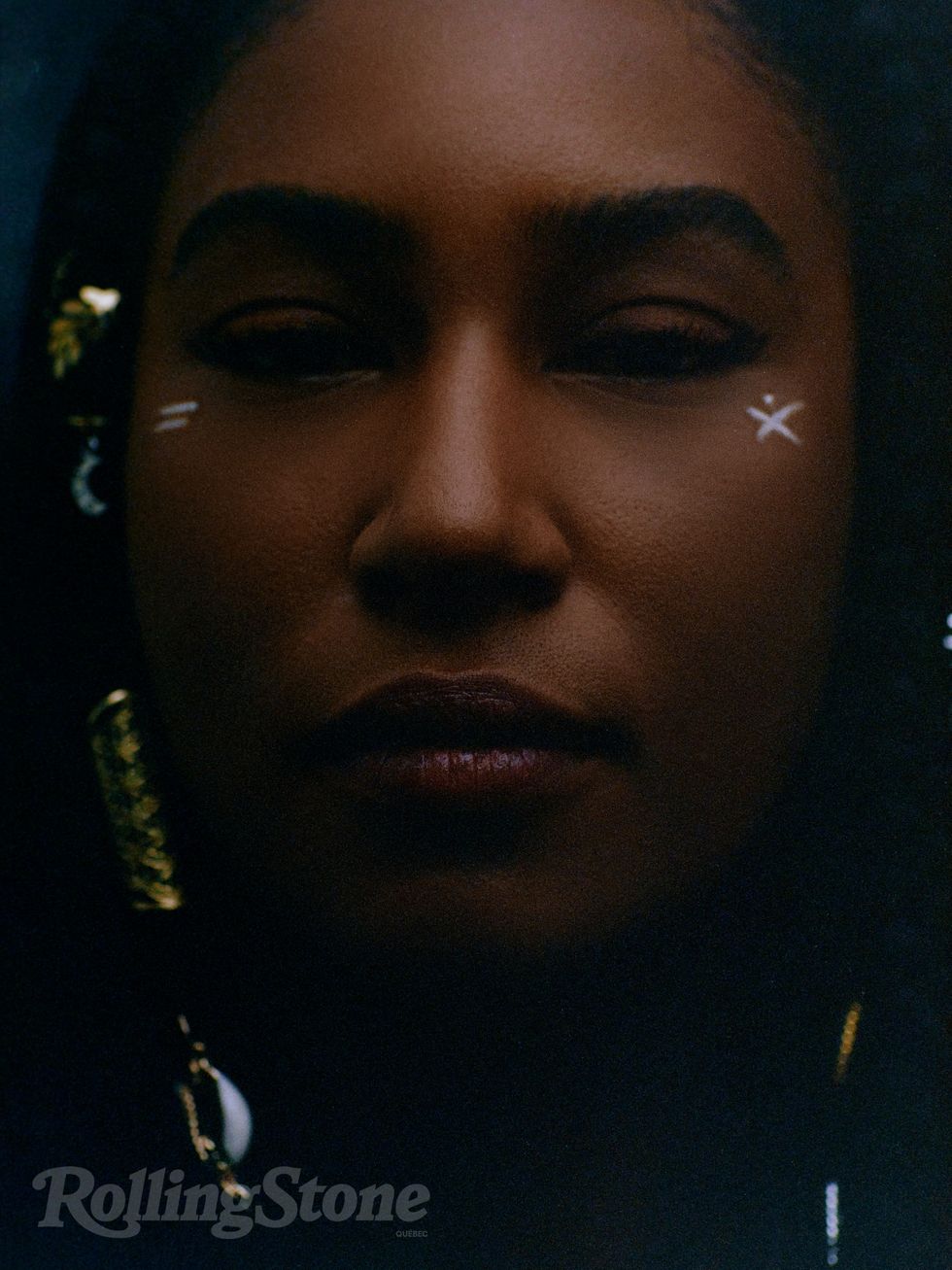

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé

Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection  Jewelry: Personal Collection

Jewelry: Personal Collection  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

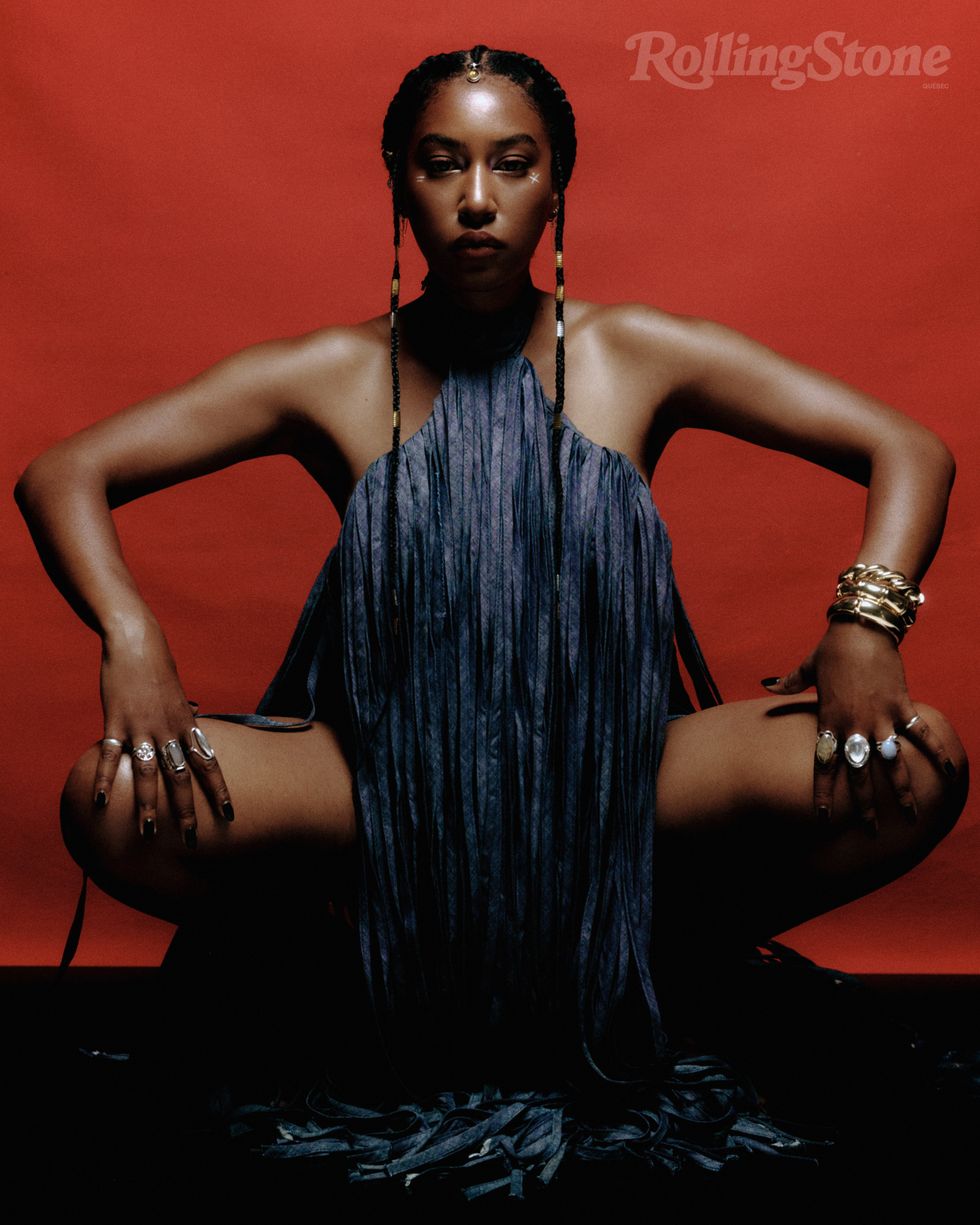

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:  Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :