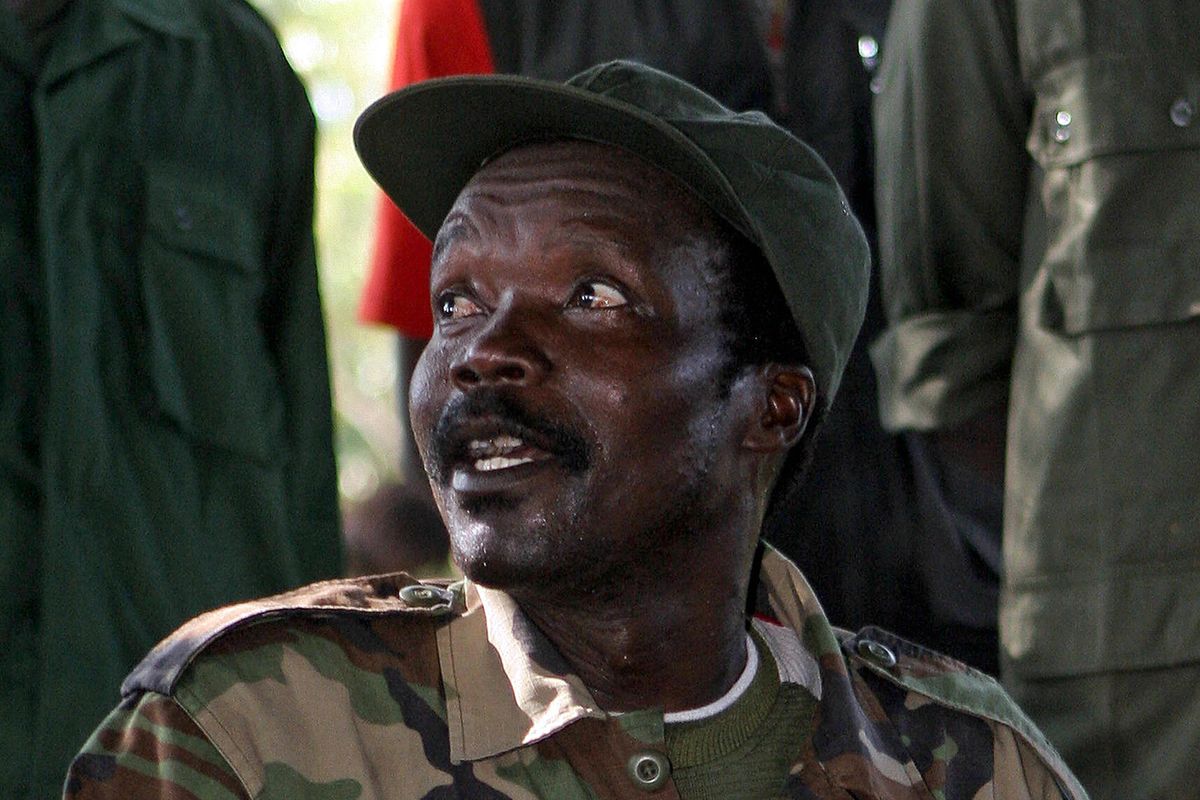

Russian mercenaries are chasing one of the world’s most notorious fugitives: the warlord Joseph Kony, who abducted tens of thousands of children from across central Africa, brutalizing and brainwashing them as child soldiers and sex slaves in a decadeslong maelstrom of terror.

Multiple sources independently describe to Rolling Stone a bloody near-capture of Kony by Russian mercenaries working for the Wagner Group, in a remote corner of the Central African Republic in early April. A social media post affiliated with Wagner also confirms some aspects of the group’s interest in the warlord.

“This amounts to hot pursuit [in] the African bush,” says a U.S. source familiar with efforts to capture the warlord. “The U.S. military got within 72 hours of Kony. Wagner may be even closer.”

The operation demonstrates Russia’s ever-expanding reach across Africa, and also illustrates the shortcomings of more than two decades of U.S. military strategy on the continent. Despite spending billions on counterterror operations, training, and infrastructure in Africa since the beginning of the Global War on Terror, extremist violence is at an all-time high, according to researchers at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, a U.S.-funded research institute. Even as fatalities from terror attacks have spiked with “a near doubling in deaths since 2021,” a string of coups and civil wars has unraveled Washington’s partnerships and created chaotic power vacuums.

American adversaries like Wagner are stepping into the breach.

The mercenary group is the de facto armed expeditionary branch of Kremlin foreign policy, and is a key player on the African continent and in places like Syria and Ukraine, directly supporting Russia’s military operations. What separates Wagner from other private military companies is that it is funded and backed by Russian state security apparatuses.

Founded by Yevgeny Prigozhin, an ultranationalist entrepreneur with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin, Wagner forces conducted a high-profile mutiny against the Kremlin last June. The central complaint of the mutineers, led by Prigozhin, was that the war in Ukraine was being mismanaged — leading to the deaths of tens of thousands of Wagner mercenaries.

The Wagner uprising, the first military challenge to Putin’s rule, ultimately proved futile. Prigozhin agreed to end the mutiny in exchange for guarantees of safety and revisions to Wagner’s role in Ukraine. Those guarantees didn’t amount to much. Prigozhin died when the business jet in which he was flying crashed in a field northwest of Moscow — only two months after the public falling out with his boss.

But Wagner itself was too valuable to cast aside. After Prigozhin’s death, the company has been placed under the direct control of the Russian defense ministry and its military intelligence branch, the GRU. Parts of its operations have been rebranded as “Africa Corps,” but the Wagner name remains in common use.

The group is especially active in Mali, Niger, Sudan, and the Central African Republic, where Wagner is adept at shoring up autocratic regimes, suppressing rebel militias, and terrorizing civilians.

But Wagner’s pursuit of the warlord Kony exemplifies a new assertiveness in Russian strategy in Africa.

Kony is a self-proclaimed Christian prophet accused of crimes against humanity and war crimes, including murder, rape, kidnapping, and torture by the International Criminal Court. The warlord rose to power in the late 1980s as a rebel leader among the Acholi people, an ethnic group dominant in northern Uganda.

To understand the Wagner operation in pursuit of Kony, Rolling Stone connected with a rebel group whose members witnessed portions of the April 7 attack and its aftermath near a village in eastern Central African Republic called Yemen (like the country). As the rebel group — UPC, or Union for Peace in Central Africa — was on the move in the hinterlands, a rebel commander named Ousmane relayed the account from fighters on the ground in a series of voice messages.

“At least four people were killed, including two civilians and two Wagner,” Ousmane says, adding that Kony was “still in the area” as of April 8.

The operation began when 14 defectors from Kony’s “Lord’s Resistance Army,” or the LRA, surrendered to a group of men posing as Central African Republic government forces at the end of March. The men were, in fact, a Chadian armed group affiliated with Wagner, which often partners with local militias to support its operations.

The defection occurred in Central African Republic’s Haute-Kotto Prefecture, a wooded savanna of more than 33,800 square miles — larger than South Carolina — with few roads and numerous isolated villages. Its dense shrublands and intricate network of rivers, streams, and pools is a haven for armed groups, ivory smugglers, and poachers, and it has long been key to Kony’s survival.

The Chadian group brought the 14 LRA members — a mix of combatants, civilians, and two children — to a town called Sam Ouandjia, where they contacted Wagner, who soon arrived in force.

Wagner forces arrested the defectors and took them to an unknown destination, says a source with expertise in the region and the LRA, who requested anonymity given security risks to individuals in the Central African Republic.

“The treatment of these defectors upset local authorities in Sam Ouandja, who have often worked with other key stakeholders to peacefully process and support LRA defectors in the past,” the source says, adding that the whereabouts of the defectors — including at least two children — remain unknown, “raising grave concerns for their safety and rights.”

The source says that only days after taking the defectors into custody, Wagner forces attacked the village of Yemen, where Kony had recently been, and which is the site of a large marijuana plantation that funds an array of regional militant groups. Locals say that Kony’s camp was within 10 miles of the village, the source says.

“We’ve been hearing about a mythical arms-and-drugs bazaar hidden in the bush as a haven for poachers and smugglers for years,” the source says. “It makes sense that Kony would want to stay close to it.”

Details of the attack were reported by locals who described a firefight that killed between two to eight people, the source said. Those accounts broadly matched those provided to Rolling Stone separately by both UPC rebels and a U.S. source.

“[Wagner] went there with helicopters, two helicopters, and they fired down at [Kony’s camp],” says Ousmane, the UPC commander. The airborne assault was followed by a ground operation, which led to a sustained firefight. “As they [Wagner] know the bush well, they did a lot of damage, they burned the entire village of Yemen. There are small villages around it, they burned all those villages. All.”

Kony was not among the fallen, the source with expertise in the LRA adds, and is believed to have escaped during or prior to the Wagner attack.

“It’s possible they weren’t that close to catching him, that Kony fled beforehand. But they certainly tried, and found a location near one of his camps,” says the U.S. source familiar with efforts to capture the warlord, and who independently confirmed details of the attack on the village.

“They also arrested a few people” including a local chief, says Ousmane, the UPC commander.

“Initial reports indicated Kony fled towards Sudan in the company of around 71 fighters not counting women and children,” says the source with expertise in the LRA. “He likely decided to change locations soon after the defection of the [LRA] group members in late March, consistent with his historic modus operandi.”

Indeed, Kony has a long history of disappearing into the bush when his pursuers get too close.

Kony created the LRA on the heels of civil war that devastated northern Uganda in a witches’ brew of genocide, rape, and murder, replete with concentration camps, total destruction of villages, and millions of refugees. The current president of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, dispatched his forces in a futile effort to destroy the LRA. The end result was a conflict that spread to the neighboring countries of South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Central African Republic.

In a simmering, decadeslong conflict in which multiple armed parties with little restraint or regard for international law regularly carried out atrocities against civilians, the LRA stood out as the most brutal of all the warring parties. Abducting children from across northern Uganda and elsewhere and indoctrinating them in Kony’s messianic personality cult, the LRA filled its ranks with child soldiers. The children were dehumanized through calculated brutality aimed at desensitizing them to violence and bloodshed.

Multiple efforts to negotiate an end to the LRA’s campaign of horrors led nowhere, and by the late-2000s, stopping the group had become a global cause célèbre, akin to efforts to stop the genocide in nearby Darfur.

By 2008, the U.S. State Department had dubbed Kony a “specially designated global terrorist,” and the Pentagon was providing intelligence and operational support to Uganda to capture him. When those efforts failed, the U.S. military became directly involved.

On the orders of President Barack Obama in 2011, U.S. Army Special Forces led the American pursuit of Kony in an operation called Observant Compass. Many ongoing U.S. military operations in Africa have a broadly defined counterterror focus that emphasize air strikes, intelligence gathering, and training local partner forces to tamp down on the activities of extremist groups.

Observant Compass had a much simpler directive: Kill or capture Joseph Kony.

“This is a unique mission in the sense that — for a soldier that’s been in the army for a few years — this is one of the most clearly defined, succinct missions I have been associated with,” Lt. Col. Matt Maybouer, the forward commander of a special forces base in Entebbe, Uganda, told this reporter on a visit to the operation in 2016. “Because it came directly from the president.”

Observant Compass — like the other counterterror operations in Africa — provided the impetus for the U.S. to organize a sprawling network of bases, airfields, and supply networks in some of the world’s most inaccessible terrain. The counter-LRA operation alone was spread across five countries in central Africa, costing an estimated $780 million.

But, despite offering up to $5 million for information leading to Kony’s capture, and significant success in capturing LRA splinter groups and reducing the militant group’s influence, the warlord remained elusive.

Observant Compass was wound down by former president Donald Trump after he took office in 2017, and Uganda also ended its counter-LRA efforts, reasoning that the group and its offshoots had permanently fled across the borders and weren’t coming back.

Enter Wagner.

The group has one of its largest operations in the Central African Republic, where more than 1,000 personnel support the government of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra in exchange for natural resource concessions — giving Wagner effective control over mines that are a lucrative source of gold, precious metals, and other minerals.

These concessions are “key to financing Wagner’s operations in the [Central African Republic] and beyond,” including in Ukraine, according to the U.S. government.

“The Wagner Group exploits insecurity around the world, committing atrocities and criminal acts that threaten the safety, good governance, prosperity, and human rights of nations, as well as exploiting their natural resources,” the U.S. Treasury Department wrote last year, announcing it had sanctioned numerous individuals and companies assisting Wagner with its operations in Africa.

Afrique Média TV, a Kremlin-linked media outlet that serves as a primary source for information about Wagner activities in Africa, has not discussed the incident or the mercenary group’s apparent interest in Kony. But on April 21, a Telegram channel known to be used by Wagner posted a statement saying the mercenary group had conducted an operation freeing “14 children enslaved by the terrorist group LRA for eight years.”

“During the operation, two generals, a colonel and six LRA militants were killed and weapons and ammunition were captured. Russian specialists transported the children safely to Bangui, where they are currently in the instructors’ camp awaiting the process of returning home,” the statement said.

A Wagner operative named “Viktor” — a pseudonym — known to be in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic, did not respond meaningfully to Rolling Stone’s requests for comment. Efforts to reach a separate Wagner field operative in the Central African Republic by cellphone were unsuccessful.

The recent experience of an Italian adventurer in the Central African Republic suggests the group may be trying to soften its image in Africa.

Niccolò Monica has a unique perspective on Russian mercenary operations in Africa: Earlier this year, he was detained by Wagner in the Central African Republic, spending several days as their prisoner.

Monica, who was traveling overland from Cameroon to Chad through the Central African Republic as part of his long-term goal to visit every country in the world, was stopped by police at a checkpoint just 30 miles from the Chadian border, after days of travel through a perilous region that is rarely visited by outsiders.

“I like to cross borders,” Monica tells Rolling Stone. “They are always such an interesting geographical component. I cross many borders by land.”

Monica told the police he was a tourist. “They didn’t believe me,” he says.

Security forces were dismayed to encounter such an unusual visitor. They took Monica and his motorbike-taxi driver into custody, and called in Wagner.

“When I saw this group of giant, heavily armed soldiers coming towards me and saw the Wagner red skull logo on their hats, I thought I was dead,” says Monica. “For the first few minutes, I was very shaken, and the situation was quite surreal, but after five minutes, everything was much more chill. They didn’t handcuff me or use force — they just asked me to follow them. They didn’t try to get physical.”

The mercenaries took Monica to their operating base, where he was thoroughly questioned, searched, and inspected for tattoos or tell-tale scars that might reveal he was more than the simple tourist he claimed to be. However, the English-speaking mercenary brought in to conduct the interrogation behaved courteously and professionally, Monica says, adding: “I really felt that they had direct orders to be kind to me.”

Monica had been able to notify an Italian diplomat of his situation by text before being taken into custody, which touched off a storm of frantic high-level inquiries about his location and status from the Italian government. He was eventually released by Wagner to Central African Republic officials, who in turn handed him over to a series of diplomats, before he was flown back to Italy.

Monica says he is aware of Wagner’s reputation, which includes accusations that they have committed war crimes and were complicit in the assassination of three Russian investigative journalists in the Central African Republic. He thinks the treatment he was afforded was designed to send a message.

“One of the guys told me, ‘You see? Wagner is good. We made coffee for you and gave you nice friends to talk to,’” Monica says.

Such image-burnishing fits with the goal of the Wagner Group — and by extension, the Kremlin — of demonstrating it is a reliable partner in Africa. By backing Wagner’s security operations, Moscow not only gets a ready source of hard cash used to personally enrich Putin’s inner circle of siloviki — or security-state oligarchs — it also gains a lever of influence in countries like the Central African Republic and Syria. This is essential for Putin’s strategy to supplant and diminish Western influence globally.

Overall, U.S. strategic-military partnerships in Africa developed over the years of the Global War in Terror have begun to disintegrate. Key components of the American counterterror strategy have unraveled — including in Niger, where the leaders of a recent military coup are demanding that the U.S. withdraw, and in Mali, where the French military was also forced to withdraw after a military coup. Meanwhile, protesters across multiple African countries can now be seen carrying Russian flags and calling for the deployment of Wagner.

If Wagner were to catch a warlord that an American president personally ordered the Pentagon to kill or capture, to no avail, it would only further humiliate the U.S. It would also bolster Wagner’s image, demonstrating to governments that there is an alternative to Western intervention.

One former military officer familiar with U.S. operations targeting Kony admits that the Russian operation shows the mercenaries are on the right track: “It’s not the end of the Kony story, but it’s a continuation — and Wagner may give us the ending.”

The officer wryly notes there may be complications if Wagner accomplishes what American special forces could not. “How ironic would it be if the U.S. has to pay Wagner the $5 million bounty for catching Kony?” he says.

Legal hurdles would make such a payment unlikely, but U.S. government lawyers may soon have an opportunity to work such details out, he adds.

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:  Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :