On their new album Hotel Caracas, Mau y Ricky reconnected with their roots in more ways than one: The Montaner brothers packed their bags and flew to Caracas for the first time in 15 years, rekindling their love for a place they left as kids. As they became inspired by their home country, they started making music that rekindled their “love of writing and making music” for the sake of making it, without the pressure of commercial success.

Put simply by Ricky: “It really just fucking changed our lives.”

On their new album, their first under their own label, the brothers stepped away from any expectations while staying true to the catchy pop melodies and playful lyrics they’re known for. The pair experimented alongside producer Malay, known for his work with Frank Ocean and Zayn, and the resulting 15-track project, out Friday, brings them fully out of their comfort zone.

“When you start tasting certain levels of success, it sometimes can start conditioning your way of creating in the studio because you are just creating with expectation,” Ricky tells Rolling Stone. “And that hinders your creative process, because you’re almost trying to write for a playlist or for the club.”

“We were able to find this really sweet spot of creating out of the love of it and the joy of just adding to the record, versus being like, ‘How do we make sure this shit is huge?’” Mau adds.

Over the last year, the pair returned to Venezuela multiple times. They filmed a tearful documentary, due later this year, that shows how they rediscovered where they were born, and recorded 15 music videos for Hotel Caracas, backed by a massive crew filled with local creatives. The two fled Venezuela with their father and Latin music legend Ricardo Montaner, for Miami, where they grew up and have spent most of their lives. Their memories of Venezuela are sparse, but they remember hearing often that there would “never be any way for us to go back.”

“We started suffering from a major identity crisis without really knowing, and we would just mask it with anger in a way,” admits Ricky. He says his Venezuelan friends would joke about their Americanized accents sometimes and call them “gringos.” It wasn’t until Mau had his baby that the pair decided that maybe it was time to go back. “This kid won’t know where he’s from. Where the fuck are we from, bro?” Ricky remembers asking Mau.

But returning to Venezuela truly felt like returning home. “When you are where you were made, it’s almost as if things flow naturally. We felt like we were a part of it all always,” Mau says. “There, I felt en mi salsa.”

The visuals pair well with the album itself, which explores electro-pop and house sounds on tracks like “Pasado Mañana” and “David Beckham.” On “Wow,” they test out tropical flows, and the standout “Espectacular” even features merengue legends Ilegales. On “Vas a Destrozarme,” the guys effortlessly lace banda horns with R&B, a mix inspired by Malay seeing Chiquis perform banda at the Latin Grammys. “It’s this R&B, bluesy, banda record. It’s such a crazy [track] because those horns transmit such an emotion,” Mau explains. “It fucks you up.”

Mau y Ricky played most of the instruments on the album themselves, and recorded some of it on tape, giving the music a texture they never anticipated. “It required you to be on your A-game,” Mau says.

Some lyrics on the album explore infidelity, vices, and other themes “they would’ve never touched on before.” Mau remembers how missing his son on a long trip to L.A. inspired him to write “Amarte Tanto” with Canadian singer-songwriter J.P. Saxe, who’s also featured on the project and introduced the duo to Malay. “I feel like right now I’m going through this thing with my son where I can’t believe how much it hurts to love this kid,” he remembers telling Saxe. “And it hurts because it’s a painful love, I don’t know how to explain it.”

Ricky points to “Cancion 2” for featuring his most personal story. On it, he expresses gratitude for meeting his wife at the right time, and not when he felt “lost” and was hanging out with two or three girls at a time. “We weren’t open to being as honest before,” he says.

“It’s all honestly based on us wanting to transmit feelings,” Mau adds. “It’s been a beautiful, beautiful, beautiful process to go about music in that way.”

Coat (polyester and wool), shirt (silk), Dries Van Noten, SSENSE.com / Flower (silk), M&S Schmalberg

Coat (polyester and wool), shirt (silk), Dries Van Noten, SSENSE.com / Flower (silk), M&S Schmalberg

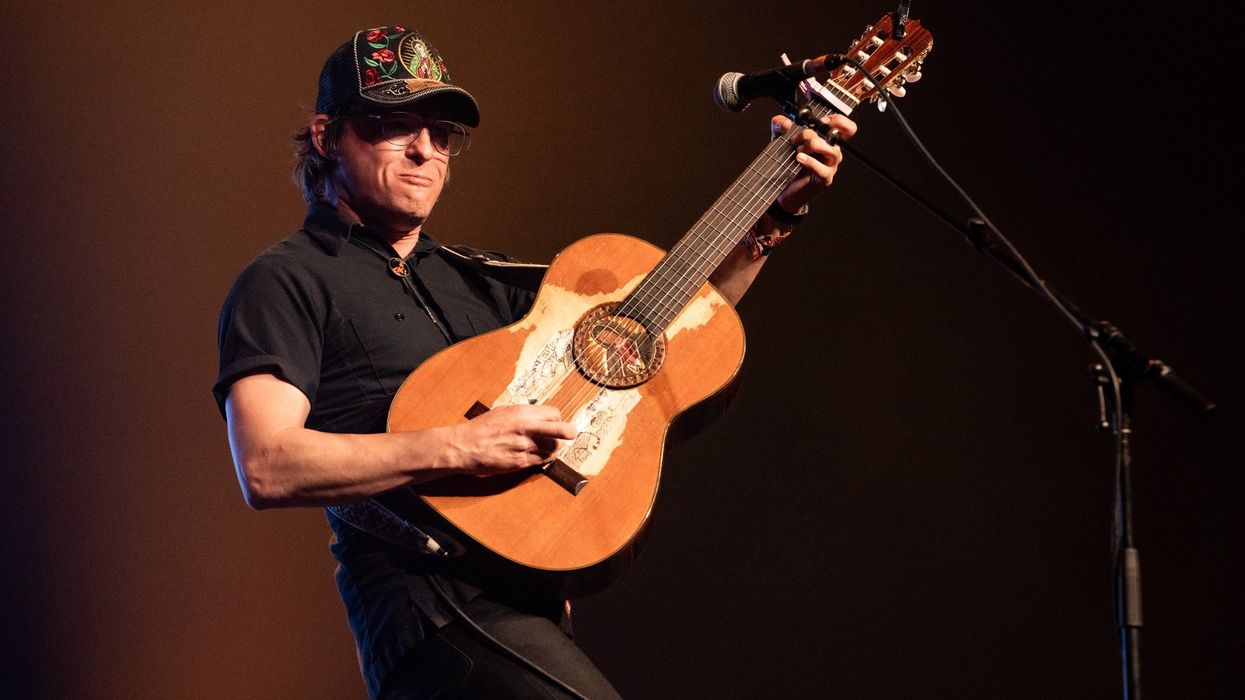

Blouson (denim and hand embroidered patches), WJ Crosson / Shit (polyester), Homme plissé Issey Miyake, Holt Renfrew/Pants from personal collection/ Shoes(canvas), Marni

Blouson (denim and hand embroidered patches), WJ Crosson / Shit (polyester), Homme plissé Issey Miyake, Holt Renfrew/Pants from personal collection/ Shoes(canvas), Marni Jacket and pants (virgin wool), shirt (acrylic coated cotton), Moschino / Shoes from Pierre Lapointe's personal collection

Jacket and pants (virgin wool), shirt (acrylic coated cotton), Moschino / Shoes from Pierre Lapointe's personal collection

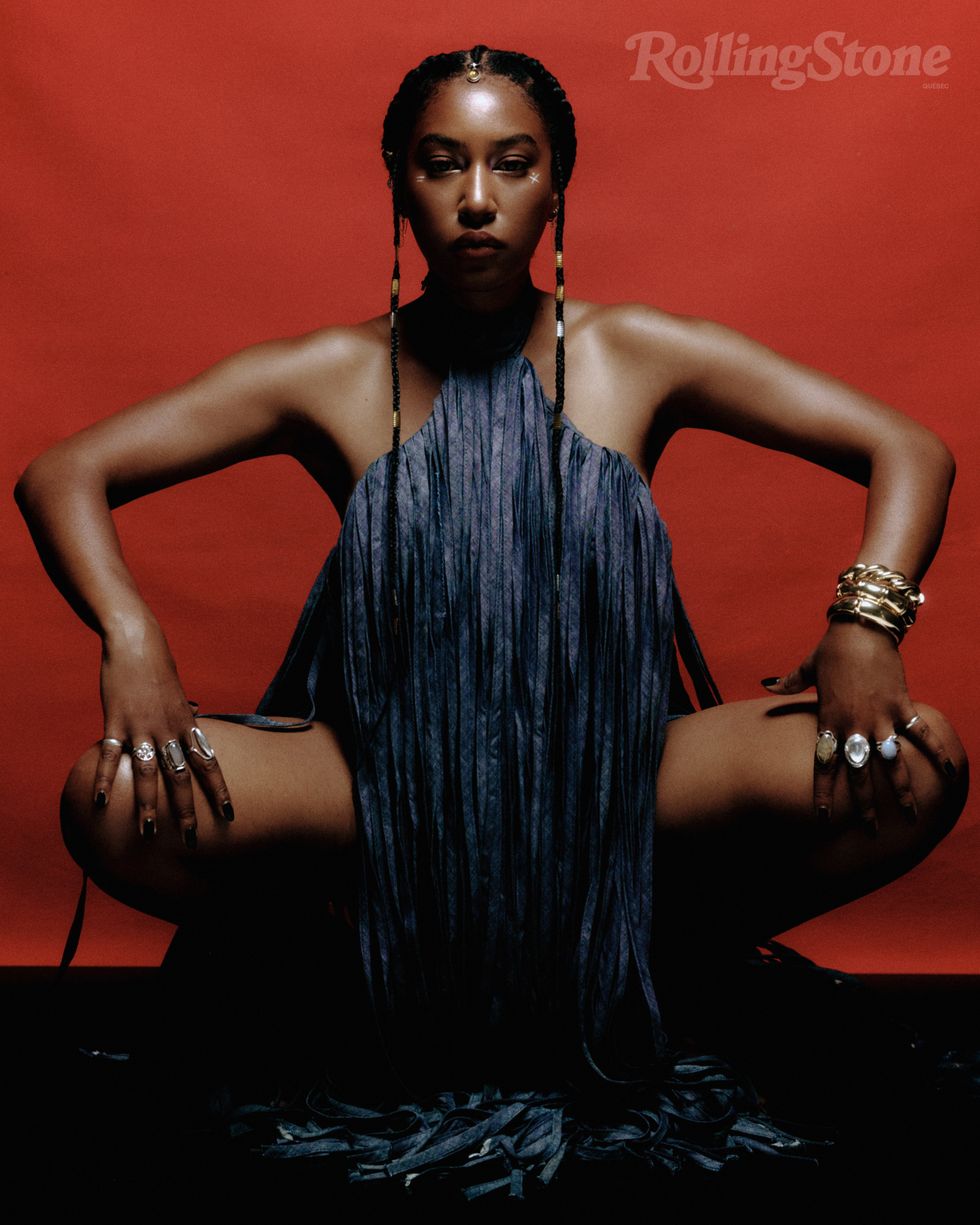

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé

Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection  Jewelry: Personal Collection

Jewelry: Personal Collection  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

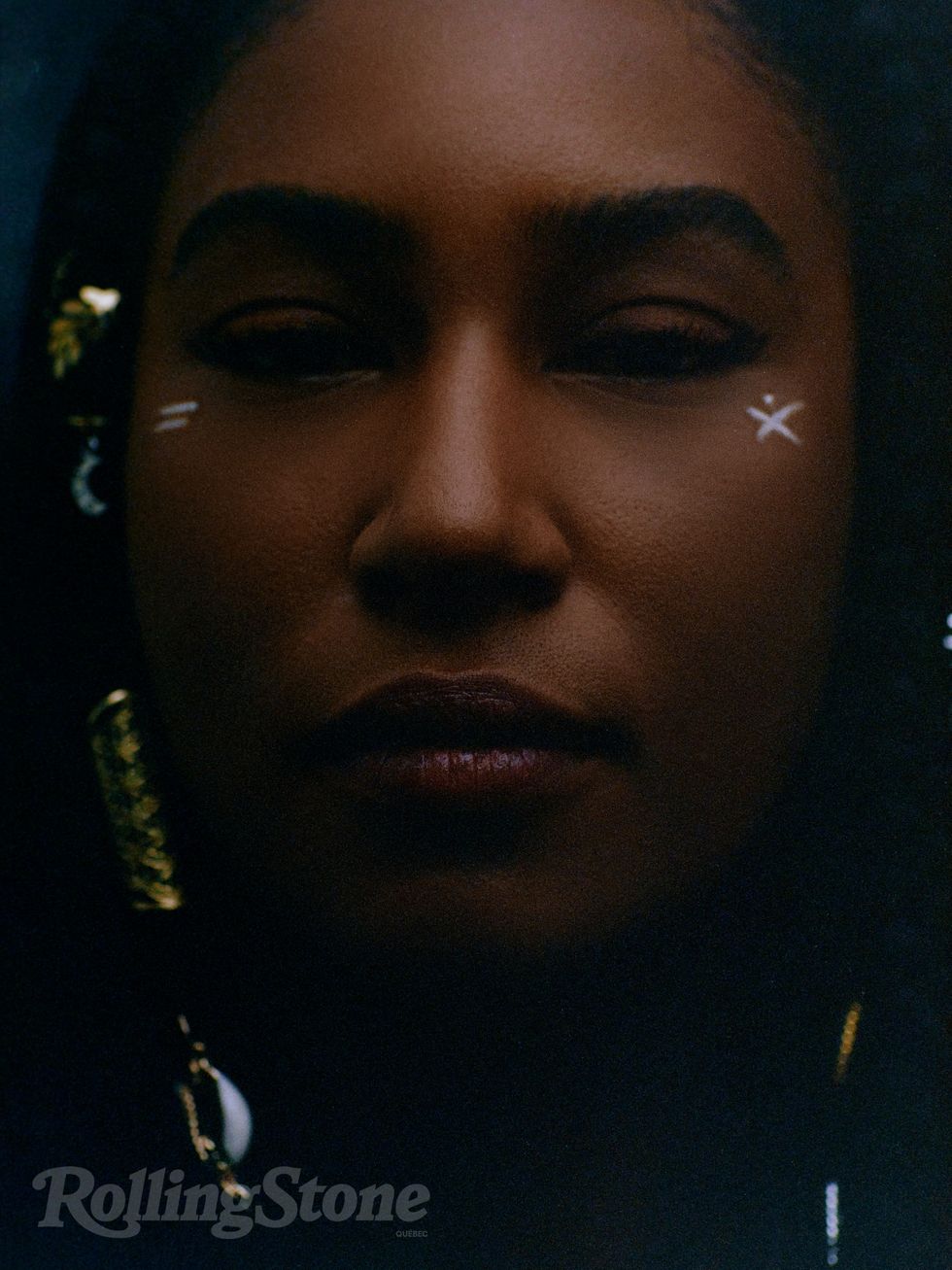

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:  Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :