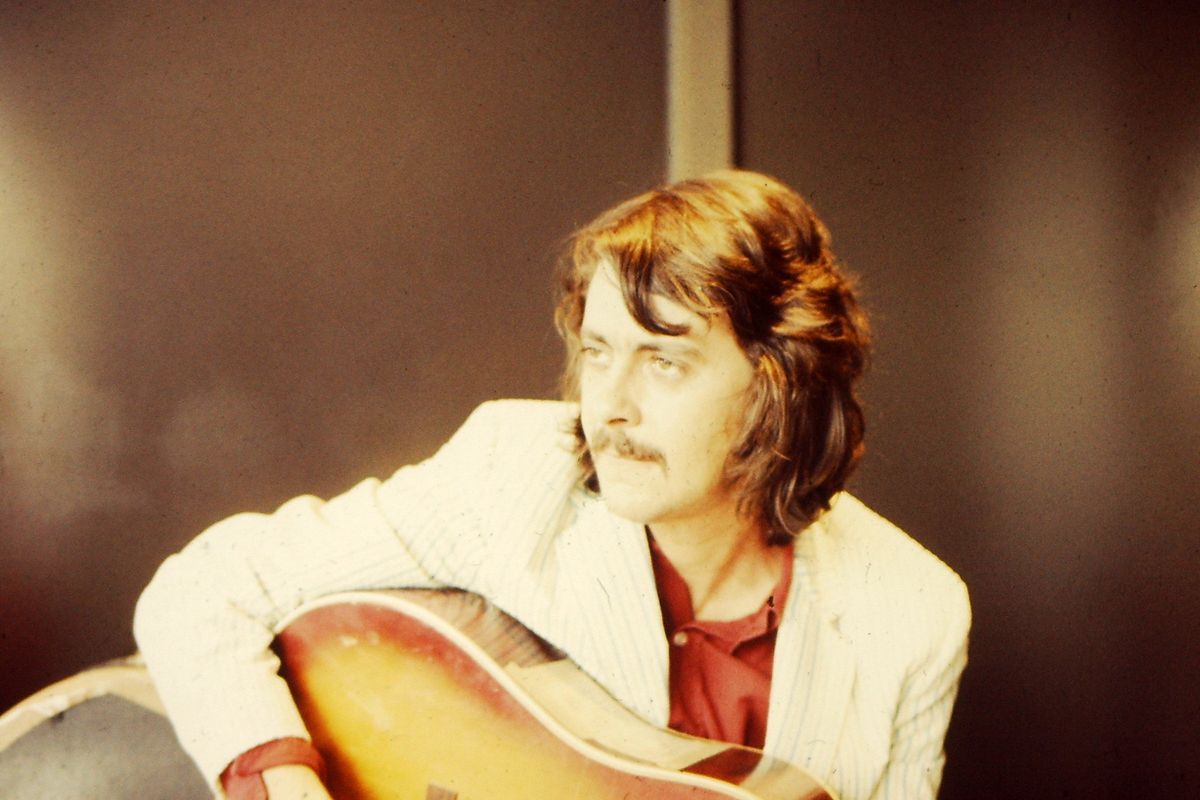

Right up until his death in 2022, Bob Neuwirth was known to cognoscenti as a songwriter (“Mercedes Benz,” famously recorded by Janis Joplin), painter, recording artist, and onetime member of Bob Dylan’s inner hipster circle. The last thing he was known for was being famous, which his longtime partner, music executive Paula Batson, says was intentional. “He was very self-effacing in a way,” she says. “He didn’t believe in blowing your own horn. He loved promoting other people and helping them, but he wasn’t good at self-promotion.”

Two years after he died of heart failure at age 82, Neuwirth’s profile is about to increase beyond his appearance in D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back. In December, actor Will Harrison (who played Graham Dunne, the lead guitarist in the streaming series Daisy Jones & the Six) will be seen playing Neuwirth in A Complete Unknown, the Dylan biopic starring Timothée Chalamet. A documentary on Neuwirth’s life, co-produced by Batson and currently in the works, will incorporate footage from a posthumous 2022 tribute concert that featured covers of his songs by Eric Clapton, T Bone Burnett, Maria Muldaur, the late Happy Traum, and many others.

On the next edition of Joni Mitchell’s rarities boxes, Joni Mitchell Archives, Vol 4: The Asylum Years (1976-1980), Neuwirth will be heard introducing Mitchell on several performances recorded during the Rolling Thunder Revue. Over 1,000 pieces of his paintings and artwork have been catalogued. And Neuwirth’s own debut album, first unveiled 50 years ago, has been remixed and will be re-issued next month, accompanied by a new lyric video featuring rare footage, most of it shot in the Sixties by Neuwirth himself.

An art student at the School of the Museum of Fine Art in Boston, the Ohio-born Neuwirth wound up in the Cambridge and then New York folk scenes. “Right from the start, you could tell that Neuwirth had a taste for provocation and that nothing was going to restrict his freedom,” Dylan wrote admiringly in Chronicles: Volume One; indeed the two shared a love of a cynical putdown. But Neuwirth could also be supportive, encouraging Patti Smith to write songs and not just poems and suggesting Joplin record his friend Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee” when the song was largely unknown.

Eventually leaving the Dylan orbit (although returning for Rolling Thunder), Neuwirth moved to L.A. There, he fell in with the Troubadour crowd and wound up being signed to David Geffen’s Asylum label alongside Dylan and fellow Laurel Canyon regulars Mitchell, the Eagles, Jackson Browne, David Blue, and Judee Sill. Arriving a decade after he’d first played clubs in New York, his first and only Asylum album, Bob Neuwirth, was the definition of a long-delayed debut.

But with Geffen’s financial encouragement, Neuwirth made up for lost time. Attesting to his stature, Neuwirth recruited a veritable denim-clad army to join him on the songs, including Kristofferson, Cass Elliot, Don Everly, the Byrds’ Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman, Rita Coolidge, then-Poco member and future Eagle Timothy B. Schmit, folk legend Geoff Muldaur, steel player (and Neil Young compadre) Ben Keith, then-Doobie Brother Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, and Dusty Springfield. Neuwirth, McGuinn, and Kristofferson cowrote “Rock and Roll Time,” a boozy slice of Seventies music life, and Neuwirth also finally was able to release his version of “Mercedes Benz,” which he never considered much of a song, and with a new verse.

Befitting the times, the album sessions were reportedly carousing affairs. “He said it was just a drunken alcohol fest,” says recording engineer and Neuwirth friend John Hanlon. “It was the Seventies. The label gave him a lot of money, and you could tell. Nobody questioned budget with them. It was just about making great art.”

But according to Batson, Neuwirth was never happy with the end result, which was overloaded with guests and layers of instrumentation that swamped Neuwirth’s voice. The album also reflected his own indulgences at the time. “As long as we were together, Bob would mention how amazing it was to have Don Everly and Mama Cass and Kris’ band and Booker T. Jones at those sessions,” Batson says. “But he knew that the end result was not what it could have been. He wasn’t happy with it because he felt that, not being sober, he didn’t deliver what he could have. It was a regret.” In fact, Neuwirth stopped drinking three years after the album’s release.

Shortly before his death, Neuwirth thought about revisiting and tweaking the album and reached out to Hanlon, who has worked for notorious audio perfectionist Neil Young for decades. “I said, ‘How do you want me to approach this?’” Hanlon recalls. “And Bob said, ‘I know what you do. Just do what you do.’ He was a man of few words about music, but he knew what was good and what sucked.”

Working painstakingly with the tapes, Hanlon was able to pare down some of the horns and orchestration and declutter the recordings. “These were A-list players, all playing great licks, but everyone was playing constantly,” he says. “You had to figure out the lick that accentuated the melody and what the melody line was. I wanted to find the song in the song and bring it out.”

With the help of the remix, Bob Neuwirth sounds even more like an early alt-country record, especially on “Kiss the Money” (which is getting the lyric-video treatment), the waltz “Hero,” and Neuwirth’s takes on country songs by Don Gibson (“Legend in My Time”), Donnie Fritts, and Troy Seals (“We Had It All”). The reissue, which will be released on CD and vinyl on Sept. 27 and then on streaming services in January, will also include “Ohio Mountain Blues,” an outtake that finds Neuwirth singing about leaving “a little old country town” for, ultimately, New York City.

Neuwirth passed away any of this renewed interest was in the air. The bulk of the work on A Complete Unknown didn’t start until after his death. (Batson says she hasn’t seen any of the movie yet but adds, “I’m happy to see Bob included and I hope it’s wonderful.”) The same goes with the revamped Bob Neuwirth album; sadly, Neuwirth was never able to hear a note of his dream project. But Hanlon feels his friend is aware of it, somehow. “I know he’d be proud of it,” he says. “As far as I’m concerned, he has heard it in his own way. He’s heard a bit of it in heaven.”

Coat (polyester and wool), shirt (silk), Dries Van Noten, SSENSE.com / Flower (silk), M&S Schmalberg

Coat (polyester and wool), shirt (silk), Dries Van Noten, SSENSE.com / Flower (silk), M&S Schmalberg

Blouson (denim and hand embroidered patches), WJ Crosson / Shit (polyester), Homme plissé Issey Miyake, Holt Renfrew/Pants from personal collection/ Shoes(canvas), Marni

Blouson (denim and hand embroidered patches), WJ Crosson / Shit (polyester), Homme plissé Issey Miyake, Holt Renfrew/Pants from personal collection/ Shoes(canvas), Marni Jacket and pants (virgin wool), shirt (acrylic coated cotton), Moschino / Shoes from Pierre Lapointe's personal collection

Jacket and pants (virgin wool), shirt (acrylic coated cotton), Moschino / Shoes from Pierre Lapointe's personal collection