It’s 2004 in Pomona, California, and 700 people are gathered in a hall at California State Polytechnic University to compete in a fighting-game tournament. From across 30 countries, fans of the era’s biggest games like Marvel vs. Capcom 2 and Tekken Tag Tournament have piled into the venue for their chance at glory — not for big money, the prize pool is practically nothing for the hobbyist event — but for pride. For most, it’s just another Sunday with friends, but two players are unknowingly about to cement their place in gaming history. This is the day that changes the community forever.

The event is the 2004 Evolution Championship Series (Evo 2004 for short), and it’s the site of esports’ most viral clip: a 26-second coup de grâce dubbed “Moment #37” that will be viewed over 100 million times online and inspire a whole generation of players.

In honor of the 20th anniversary of Moment #37 and this weekend’s Evo 2024, Rolling Stone spoke with the two players behind the viral clip, American player Justin Wong and Japanese player Daigo “The Beast” Umehara, who have since gone on to become esports legends, to look back on how the historic match came to be and its enduring influence on gaming.

‘The Daigo Parry’

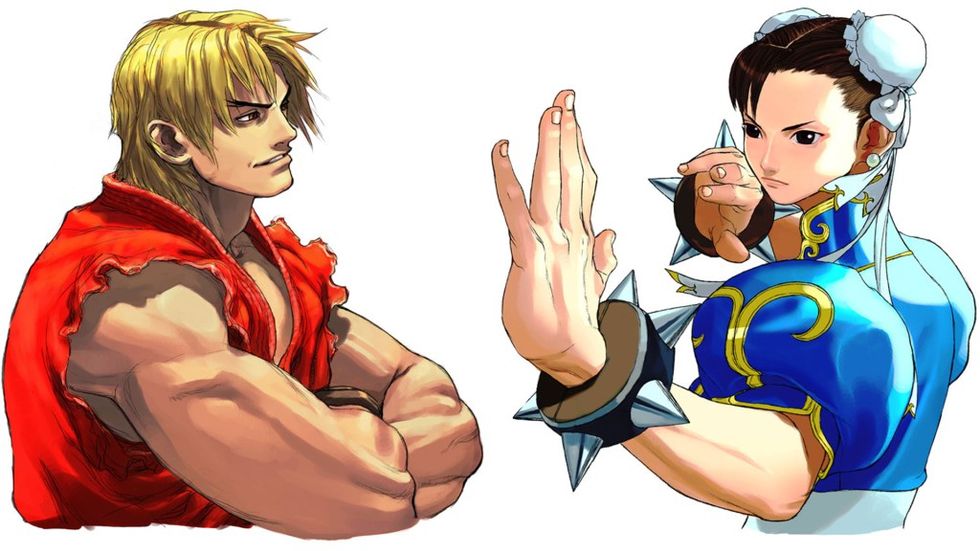

Evo Moment #37 took place during the semi-finals of the Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike tournament between Daigo and Wong and centered on a first-round match between the competitors, who previously had only known each other by name. Daigo, playing as Ken, was on the ropes after a strong start from Wong, who controlled Chun-Li. His health depleted, Daigo was just a single blow from losing the round. Confident that he could put it to bed, Wong engaged Chun-Li’s super-art move Houyoku-sen, a multi-hit combo attack that should’ve been the end, but Daigo came back to perfectly parry 17 hits in a row and unleash his own super-art, leaving everyone stunned.

For non-gamers, it can all sound like a lot of gibberish, but watching the clip it’s clear that something big had happened. Here are the basics: in most fighting games, players can block moves to avoid full damage. However, in 3rd Strike, simple blocking will still result in chip damage (i.e. lessened damage but not total immunity). In Daigo’s position with limited health, even a block would’ve ended in defeat. Instead, he had to utilize a perfect parry, executed by pressing forward into the attack, to nullify it. In this instance, Daigo needed to time 17 maneuvers within milliseconds of each blow, then initiate his own counter offensive. For many, it had never even been heard of — Wong included.

“Back in the day, compared to now, we were bad at fighting games,” Wong says, “We were good at the time, but when you think about how much fighting games have progressed, and how people can learn fighting games so much faster — the understanding of it — we were bad.”

Like it was for most players at the time, competing in traveling tournaments was just a hobby for Wong. Working at New York toy store FAO Schwarz, he spent his spare time hanging out with friends in the then-grassroots fighting game scene at arcades like Chinatown Fair. Without tons of internet FAQs and forums, they garnered most of their techniques from experience and word of mouth. Wong says he hadn’t ever seen the move, which became known as the “Daigo Parry,” therefore had no idea it even existed.

“People spread rumors,” Wong says. “People are saying, ‘You know, Chun-Li’s super, it’s unparryable. So, in my head, I believed that. It’s like the Mythbusters of fighting games. I’m brainwashed [to think], if you have low health, I could throw the super out and you lose. From every tournament leading up to Evo 2004, I never got parried. Little did I know that myth was [about to be] busted.”

Conversely, in Daigo’s circles in Japan, the technique was more widely known. He tells Rolling Stone that he learned the parrying method while practicing at a friend’s house and thought it would be something flashy to show off. For him, it was more obvious.

“Anyone who was into 3rd Strike and played it seriously would have known I could’ve made a comeback by parrying the Houyoku-sen,” Daigo says via translator. “Whether I could pull it off was another story. But, in those days when the internet was less prevalent, there was a big info gap between the U.S. and Japan, so I figured Justin probably didn’t know. I sensed that he thought his win was a sure thing.”

The community impact

Ironically, Daigo hadn’t even been training to compete in the 3rd Strike tournament that year, instead focusing his energy on other games like Guilty Gear and Capcom vs. SNK 2 for an earlier event. He claims that his victory was based purely on muscle memory. It also was intended to be his final competition.

“I’d always thought of fighting games as my special skill and something I loved more than anything else,” Daigo says, “But at around age 21 or 22, I watched all my peers give up video games as they moved on and found careers. [I] made up my mind to quit gaming once and for all. Because it hadn’t served me; it didn’t take me where I wanted. I went to Evo with the intent of it being my last time playing, regardless of how well I did.”

That all changed after the match. Daigo admits that, as a foreign player competing in the U.S., he didn’t always feel welcome at major events. With his miraculous feat, however, the tides shift in an instant.

“The player pool skewed much more toward Americans than it does now,” Daigo says. “It was like the Japanese players were [seen as] imposing upon the event, and there were no cheers for the ‘away’ team. Justin had 100 percent of the crowd’s support. The whole venue was cheering for him and wanted to see him win. But [as] soon as the crowd decided I was pretty good, they started cheering me on. People have always cheered for me ever since.”

As the American on home turf, Wong had a different viewpoint. With so many of the world’s best players being Japanese, he felt outnumbered, leaning on the crowd’s bias toward him for momentum as he worked his way through the brackets. He laments the feeling of building up the community’s support, only to have it slip through his fingers.

“I think it was just me and another American player left in the tournament,” Wong says, “and the second American player lost right away. So, it was just me left; It was like a Japanese gauntlet. So, when I’m fighting all these Japanese players and beating them, obviously the crowd was super on my side. They’re like, ‘USA! USA!’ Then I fought Daigo, [and] that’s where Moment #37 happened. And you could clearly tell it went from the ‘USA’ chant to, ‘Daigo! Daigo!’ So, he took the home-court advantage away from me.”

One of the biggest misconceptions of the match is that Moment #37 led to Daigo taking home the championship, but as Wong is quick to point out, it wasn’t even the finals. It was a battle for the loser’s bracket, leaving Wong in third place overall and sending Daigo to place second after losing to Kenji “KO” Obata, who was that year’s champion.

“I feel bad for [Obata],” Wong says, “because people don’t remember or [even] realize that he [was] actually the winner of EVO 2004 for 3rd Strike. Moment #37 just outshined his [victory].”

Although the reaction in the room was huge, the impact of Moment #37 was lost to those in attendance. For them, it was just another cool comeback to talk about with friends. Even the name is a misnomer, with “37” being randomly assigned by ring announcer Ben Cureton to appear as just another major highlight from the event during the video clipping. In the years before YouTube or Reddit, it mostly spread online in a small way through FGC (fighting-game community) networks. It wasn’t until a few years later that it circulated more heavily to become a viral clip.

“I was still young at the time, so I didn’t really think too much about it,” Wong says. “I didn’t think about what the word ‘viral’ meant. Viral was not a thing back in the day, right? There were no socials or YouTube. I don’t think [it] blew up until at least after 2010. There was like six years [where] that moment happened, but nobody really talked about it.”

Daigo had a similar experience, claiming that it was nearly a year after the tournament when a friend told him that the clip had been picking up steam online. Both players were surprised by the video’s popularity online but, looking back, now appreciate its role in invigorating the fighting game community through mainstream exposure to new audiences.

“It’s kind of like Fight Club,” Wong jokes. “You just don’t talk about Fight Club or whatever. That’s what the fighting game community was like back in the day. But once YouTube came out, when people started being able to live stream of Ustream.tv and Justin.tv (which later became Twitch), that’s when more people started going to the locals, the regionals, majors — that’s where things got a lot more exciting.”

Evo goes viral

Although esports have steadily increased in popularity in the 20 years since Evo 2004, there haven’t been many viral moments that have crossed over to garner mainstream attention. Unlike traditional sports like football or basketball, which most people in the U.S. learn to play at a young age, the familiarity with many games at the competitive level doesn’t register with casual viewers. For most, there may simply be too much to take in when watching a match of League of Legends or Valorant. The success of Evo Moment #37 is likely due to the readability of fighting games. Even without the knowledge of the deeper mechanics — the super arts and parries — there’s a simplicity to it. Two fighters duke it out, one is nearly KO’d when a flashy move hits, the crowd roars. It’s almost universal.

Wong credits the accessibility of Evo Moment #37 for viewers as a flashpoint that spiked interest in Street Fighter and professional fighting games as a whole. The historic matchup kicked off both players’ careers. Wong would go on to become a nine-time Evo champion and is now a content creator and esports commentator, including at this year’s Evo event in Las Vegas. Daigo holds a Guinness World Record for Street Fighter wins with six Evo wins of his own and is widely regarded as one of Japan’s greatest esports players.

While the impact of Evo 2004 has loomed large over the careers of both players, it’s the continuing growth of the community that each point to as the greatest boon. There are top-level competitors today who weren’t even born when 3rd Strike was released yet were inspired by the iconic clip online to pursue esports as a dream.

“Every tournament, every time I stream, I’ll have at least one person that comes up to me and says, ‘I got into fighting games because of Moment #37,’” Wong says. “Obviously, I took the loss but when you hear stuff like that, you just can’t be mad about it. Because we’re already a small community. I started playing in the fighting game community in 2001, so coming from an Evo that started with like 400 to 500 people to [now] over ten thousand? That’s kind of crazy to me.”

Daigo agrees, although the experience is still somewhat surreal to him, some 20 years later.

“I see Moment #37 in a completely different light than the rest of the world,” Daigo says. “To me, it’s as if it happened to someone else. It’s almost like a gift I received. People do tell me it was the catalyst for them. I think the popularity of that video is why people still ask for my autograph wherever I go.”

Partially due to their language barriers, and the differing trajectory of their careers, the two players aren’t especially close. They mostly interact at major events and remain friendly but acknowledge that without the random chance of their matchup, neither their careers nor the popularity of the FGC would be where it is today.

“You don’t get to choose your opponents,” Daigo says, “so luck is also a factor in whether you win or lose. [Justin’s] a rival I fought in the early days before you could make this your living, so I know we share a common ground, and when we meet it puts me at ease, in a way. I consider him a friend who gets where I’m coming from without my having to say a word.”

The feeling is mutual for Wong, who looks back fondly on his misjudgment from the 2004 bout. Had he chosen to play differently, nothing would be the same.

“It’s definitely the best loss I have taken because I was able to help grow that community,” Wong says smiling. “[All] because of me wanting to chip out Daigo for the super. Imagine that it was just a regular match and nothing crazy happened? There’s a good chance that [many people] might not have been interested in fighting games.”

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:  Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :