Since its release in 1999, Marvel vs. Capcom 2 has become one of the most popular fighting games of all time. Known for its easily accessible play style and massive roster of 56 characters pulled from both comics and iconic gaming franchises, it’s easy to see why. But MvC2 is also infamous for its music, which many fans found to be ill-fitting, if not downright annoying. So, they came up with their own soundtracks.

With the recent announcement of Marvel vs. Capcom Fighting Collection, which includes all the mainline entries in the crossover series from 1996’s X-Men vs. Street Fighter to Marvel vs. Capcom 2, casual players and pros alike took to social media to talk about their fondest memories of the coin-op classic. But the discourse also reignited the old debate about the game’s music that’s mostly laid dormant since the 2000s, and brought back talks about the unique mixtape culture that developed within the scene through widespread modding of the game itself.

As the community prepares for the next iteration of the annual Evo tournament, taking place from July 19 to 21 in Las Vegas, Rolling Stone spoke with high level Marvel vs. Capcom 2 players from the era, including 6-time Evo champion Justin Wong, 2007 Evo champion Michael “Yipes” Mendoza, and scene fixture Chris Matrix (real name Christian Ellis) to delve into the ways custom music mods took over the community and how the resulting memes became part of the game’s enduring legacy.

The vanilla music of Marvel

First released in arcades in 1999, then gaining wider popularity on Sega’s Dreamcast in 2000, Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age of Heroes became a staple of then-burgeoning esports events like Battle by the Bay (later renamed Evo). From the beginning, the game and its music were met with skepticism from fans of the series like Justin Wong, for both some of the changes made to its mechanics, as well as the score.

“When the game first came out in arcades, everyone hated it for the first month or two,” Wong says. “If you were a huge fan of [the first] Marvel vs. Capcom, you would think that this game is like a downgrade at the start. Then more people start getting into it, but we thought, ‘The music still sucks.’”

Unlike the urban hip-hop sounds of 1999’s Street Fighter III: Third Strike or the up-tempo beats of the Tekken series, the music in MvC2 had a different energy. With acid jazz tracks filled with brass horns and lounge lizard rhythm, many found the score counterintuitive to the game’s decidedly epic moment-to-moment action.

A perfect example is the game’s most well-known track, Tetsuya Shibata’s “I Wanna Take You For a Ride,” which plays over the character selection screen. For anyone who owned a Sega Dreamcast or spent their youth at the turn of millennium in the last vestiges of the arcade scene, those seven words are unforgettable. It’s the soundtrack to middle school sleepovers and pizzeria meetups. It’s also kind of terrible.

A true earworm, it’s a quirky, never-ending loop of a song that’s equal parts annoying and affecting. But while it may have earned its place — ironically or otherwise — in the hearts of many players, the rest of the game’s music doesn’t inspire the same affinity.

“When you’re playing a fast-paced game like Marvel 2,” Wong adds, “the music doesn’t really do the game justice in terms of the crazy stuff that’s there. [When] you look at the highest level of gameplay, the music would still be better with something [epic] like [in an] anime. [We] think about anime with Marvel 2 because of how intense the matches are.”

Others, like Chris Matrix, think the issue wasn’t necessarily the music itself, but the sheer amount of time fans spent playing the game that soured it through hours of play.

“Things tend to lose their novelty,” says Matrix. “This is a game that [we] play for an extremely long time, so listening to the same soundtrack does get repetitive.”

But it wasn’t just in the arcade or at local meetups where the music burned its way into people’s heads. As Yipes explains, the widespread popularity of the Sega Dreamcast version of the game made it so that the music was inescapable, even at home.

“We literally camped out at places with the Dreamcast on,” Yipes says. “[Everybody] passed out, we’ll have the character select screen playing in the background. All we hear is, ‘I’m gonna take you for a ride’ for the whole night. We’ll wake up to that shit, brush our teeth, use the bathroom — you’ll hear that shit in the background.”

Mixtape modifying enters the scene

The Dreamcast port, which became the standard version of the game after it was introduced at Evo 2004, was also the solution to the problems with the game’s music. As a home console, the Dreamcast was easier for the average person to modify than the arcade cabinets and around 2006, players had figured out how to swap out the music in-game for Marvel vs. Capcom 2 on a system level.

“It was burning CDs on the computer,” Matrix says, describing the process of adding mp3s to the Dreamcast discs. “When I was doing it, [there] was like a tutorial. I needed a boot disc; it was a little process. It wasn’t terribly hard. A friend taught me how to do it.”

In an era before YouTube or social media, tutorials and music packs were shared in private online forums, alongside videos from the meetups. The insular nature of gaming at the time meant local groups all had their own playlists that matched their style. This mixtape creation also reflected the way music was being consumed and shared in a world before streaming. For Yipes, it was just a natural extension of the culture in the 2000s.

“You’d go out to somebody’s crib in the West Coast and [be like], ‘What the fuck? You put music in this game?’ It was a change in the culture,” Yipes says. “[Because] now I could get to hear other people’s playlists, their taste in music. [But] we would make mixes ourselves, not even in the game. I would make my little mixtapes from tape decks to CDs. It was right up my alley. That’s what everybody was doing at the time.”

Historically, the fighting-game scene in the U.S. created an intense rivalry between the East and West Coasts, which ultimately informed what music gained traction at major events. For New York-based players like Wong, Matrix, and Yipes, East Coast hip-hop artists like 50 Cent and Dipset were heavy influences on their mixes. According to Matrix, with so many East Coast players competing at the highest level, their mixtapes were the ones that’d take root.

“Most of the time, our soundtracks would take precedence,” Matrix says. “When we came over, everybody knew [we] got the hot shit. We [also] had the best players, so we had the matches everybody wanted to see.”

Unsurprisingly, not every song chosen was a banger — at least not in the intended way. Everyone who put together a mix would ultimately slip in some track meant to be played for laughs. The early grassroots events were, after all, mostly just huge hangouts. Yipes recalls that songs that began as jokes would eventually find their footing as the tracks that worked best to hype up the crowds and get certain players in the right mindset to compete.

“We used to have Sade’s, ‘Cherish the Day,’” he says. “I can’t make this shit up. While she’s singing, I don’t know what it was, it just kept me calm and I was just very graceful with my movements [playing as Storm].”

“Livin’ la Vida Loca”

The biggest meme song of the bunch also became the one most synonymous with the game for many pros: Ricky Martin’s 1999 smash single, “Livin’ la Vida Loca.” Despite initially drawing laughs, it instantly took off as a mixtape favorite after debuting during a major match for Justin Wong.

“It wasn’t my choice,” Wong says. “It was just that somebody decided to put it in, and at first, I thought that was random but [after] a while I’m like, ‘You know, the beat kind of goes pretty well.’”

Wong can’t remember who originated “Livin’ la Vida Loca” as a mixtape entry, but Yipes believes it was Chris Matrix, who takes ownership of the now-infamous selection.

“It was a first to 10 with Justin [Wong] and Sanford [Kelly] at NEC [Northeast Championship 15],” Matrix says. “And on one of my mixes that they played, there was a Ricky Martin song, “Livin’ la Vida Loca.’ There was this crazy moment that happened and when that song was playing, it really heightened that moment up. [It] makes certain matches iconic.”

The Latin pop track may sound like an odd choice, but Matrix thinks it’s perfectly aligned with the tempo of Marvel.

“Marvel is a high energy, fast paced game and there’s a lot going on,” he says. “So, when you have a fast-paced song like that, when you’re hearing it and you’re feeling the rhythm with the music, [it’s] really a vibe that’s happening right there.”

The death of Marvel’s mixtape culture

With the adoption of its sequel, Marvel vs. Capcom 3, as a main event Evo 2011, Marvel vs. Capcom 2 drifted out of the limelight — as did its accompanying mixtapes. But with a re-release coming later this year, pro players are excited to see the title’s potential resurgence and, hopefully, getting picked up by a new generation of fans. But sadly, the mixtape aspect of the game’s original run likely won’t be a part of that rejuvenation.

Matrix believes that the issue stems from the fact that the only version of the game that was regularly modded for music was the Dreamcast version, which itself isn’t readily playable on modern televisions. Modding is also far less prevalent on modern consoles like the PlayStation 5 or Nintendo Switch, two of the platforms where the collection will be released. Music itself is also consumed differently today than it was in the 2000s, with streaming completely replacing the physical media and mp3 file sharing that was essential to the practice of old school mixtape creation.

Even for nostalgia-driven events or esports meetups, the musical angle has taken a hit. With the advent of live streaming, licensed music is a huge risk for event organizers. Yipes, now a professional esports commentator alongside Justin Wong, knows this all too well. Ironically, it also means that any live streamed event forces players to use the game’s much maligned vanilla soundtrack, bringing things full circle.

“We really don’t hear the OST anymore unless we do special events that [are] going to be streamed. With DMCA going on, you can’t play none of those custom songs. So, that’s literally the only time we really hear it again. Or if we nostalgically bump into an arcade with Marvel 2, and we’re just chillin’ with the homies.” For everyone else, the easiest way to relive the glory days of Marvel vs. Capcom 2 will be to sync up a Spotify playlist to be ready for when the game drops this fall. But don’t forget to add “Livin’ la Vida Loca.”

“That shit is kind of crazy, I know,” Yipes says. “But it fits.”

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection

Jean Jacket: Repull/Jewelry: Personal collection Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé

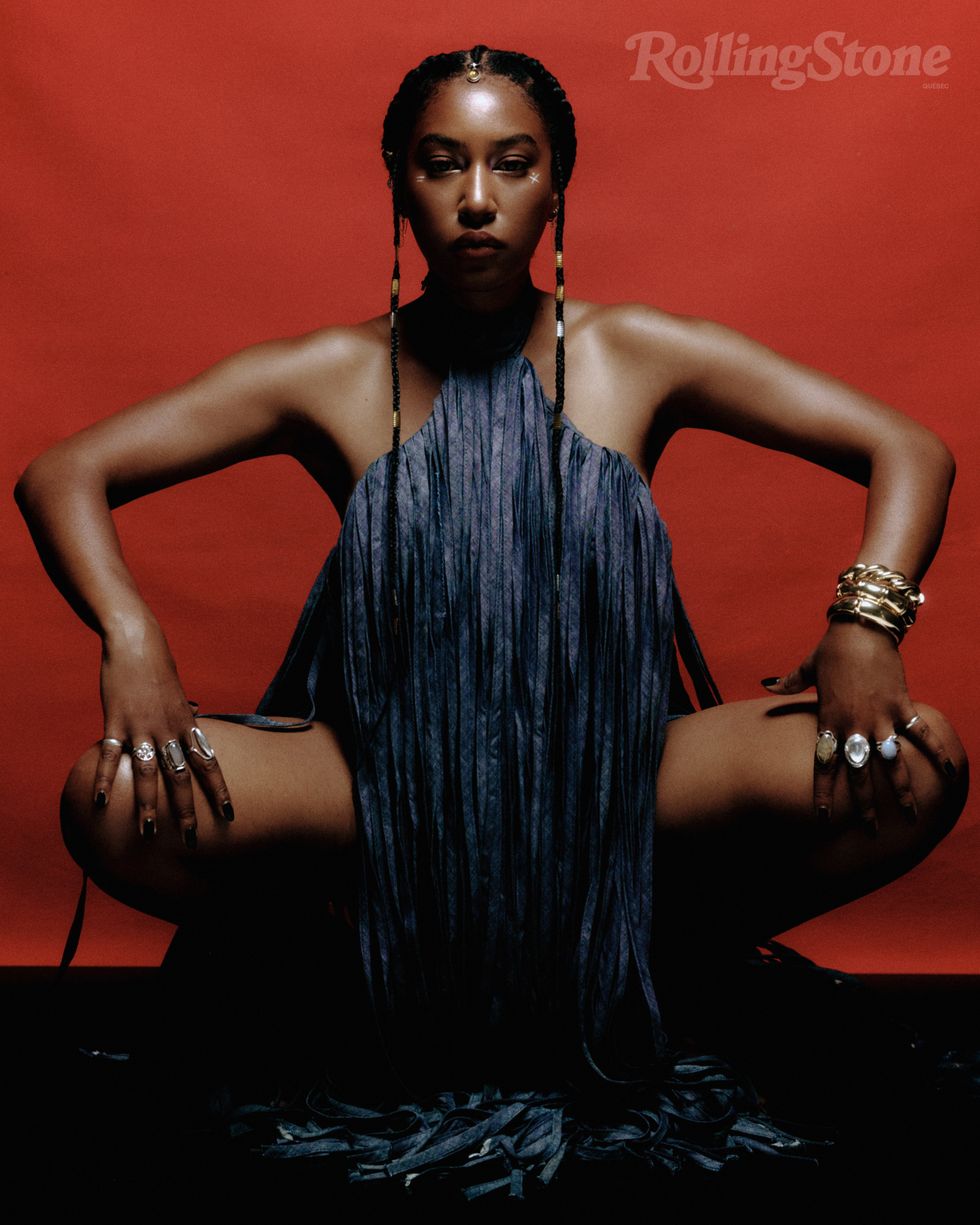

Hat: Xtinel/Dress shirt and vest: Raphael Viens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection  Jewelry: Personal Collection

Jewelry: Personal Collection  Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

Catering Presented By The Food DudesPhoto by Snapdrg0n

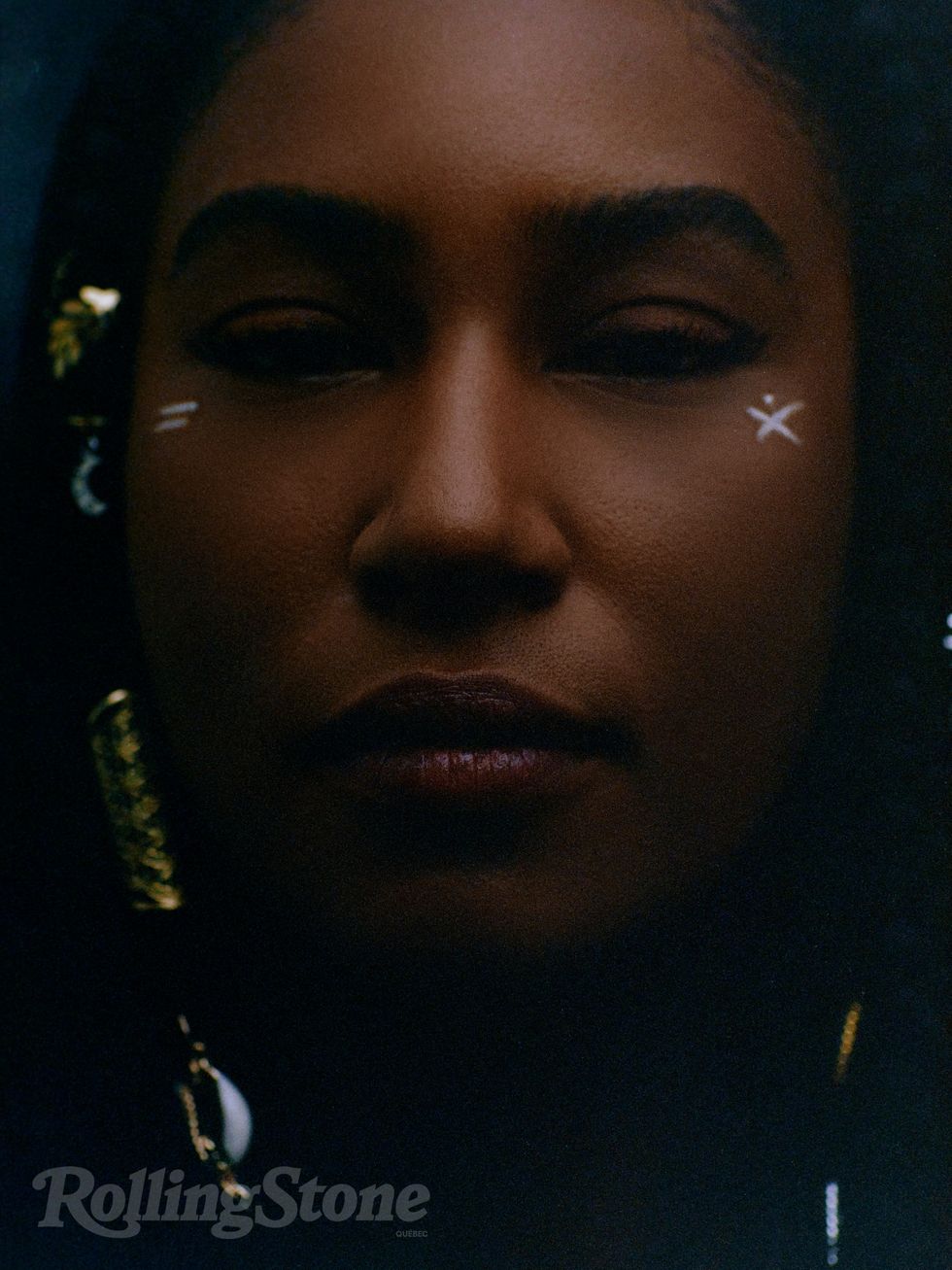

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel

Photographer: Raphaëlle Sohier / Executive production: Elizabeth Crisante & Amanda Dorenberg / Design: Alex Filipas / Post-production: Bryan Egan/ Headpiece: Tristan Réhel Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Photo production: Bryan Egan/ Blazer:  Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :

Photo: Raphaëlle Sohier/ Blazer: Vivienne Westwood/ Skirt :